To Saigon, once the languid Paris of the Orient. Is it called Saigon or Ho Chi Minh City? At the end of the Vietnam war in 1975, Saigon’s name was changed to Ho Ch Minh by the victorious communists, but many Vietnamese still refer to it as Saigon, especially in daily speech. And railway timetables and the airport use Saigon too. So as is often the case with name changes, both seem to be acceptable.

We arrived in Vietnam a few days ago on a speedboat along the wide Mekong river. It’s a fabulous, resilient and bountiful river we’ve followed on and off for many weeks since the old royal capital of Luang Prabang in Laos, where it winds through the northern hills and cascades through the islands into Cambodia. But here it ends, flowing into the South China sea in a great delta in the extreme south of Vietnam. Approaching the Vietnamese border, the riversides are great empty expanses of green and there’s lots of evidence of the controversial and environmentally damaging dredging of sand from the riverbed, it’s banks and islands. Most of it is sold to Singapore for land reclamation and the profits are pocketed by a small select bunch of cronies – it’s a familiar tale of greed and corruption.

Once across the border into Vietnam the Mekong changes its aspect, the river and its tributaries are teeming with life and it is obviously home to thousands of people. Houseboats and makeshift riverside settlements, jetties, markets and factories line the banks. It’s a colourful and bustling scene alongside river traffic that includes ferries, barges and sampans rowed by conical hatted fishermen.

We have a rough plan for our one month in Vietnam. It’s a classic route from the south to the north, Saigon to Hanoi via Dalat in the hills and the old cities of Hoi An and Hue on the coast. Vietnam has a coastline that’s just over 2,000 miles long and we’d very much like to relax for a few days on a beautiful, clean and quiet beach, perhaps an island. And we want to find somewhere memorable in the mountains.

We arrive in Saigon on a modern and comfortable bus with reclining seats, operated by the Futa Bus company. After travelling in some very dodgy vehicles in Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia, the Futa Bus experience is a pleasure and, although the driving is still appalling, we’ll book them for future trips.

First impressions. Vietnam appears relatively wealthy. Well surfaced wide roads, a really decent highway infrastructure with a few beautiful suspension bridges. Not so many cars, millions of motorbikes. I do some research. It’s a tiger economy that has enjoyed twenty years of uninterrupted growth and is currently one of the fastest growing economies in the world.

Jo has booked us into a small, comfortable and very cheap hotel in District 1 of the city, which is convenient for most of the places of interest we want to visit in Saigon as well as some decent restaurants. For the first time on this trip we are in an urban backpackerland, which is, initially, quite entertaining. There are naturally, lots of young white backpackers, and plenty of overweight tattooed subpar Anglo Saxon geezers looking like convicts on a spree. The abundant northern European faces are much harder than the smiling gent!e-eyed Vietnamese and the beer bellied men are appallingly dressed in sleeveless T shirts and ill fitting shorts.

The main street, Bui Bien, has the biggest and noisiest bars in Indochina, all with pushy touts outside. There are DJs who seem to do nothing but control the segways between tuneless, ear splitting, computer generated bass dirges. It is resoundingly awful. Conversation is impossible but unnecessary as everybody is on smartphones. The air is full of fruity shisha pipe smoke and the occasional waft of marijuana. Sleazy blokes sit at tables accumulating emptied beer bottles, like a scoresheet, and leering at the ‘working’ girls. Happy hour is four hours long and the restaurants do all day English breakfasts. This place could be anywhere or everywhere. It’s entertaining because it’s such a dreadful freak show, a zoo, in which I feel like some gawping outsider. Fatigue sets in quickly enough and we find a quiet balcony in a restaurant called The Five Oysters where we discover the excellence of Vietnamese wine which comes from the hills of Dalat – a town we plan to visit. The white isn’t great but the 12% red is soft and full of flavour, and only £6 a bottle in the restaurant (or just £3 from a general store).

Real Saigon goes on in the warren of alleys that Jo weaves through with such ease using her GPS map. I tell her that she has the intuitive orientation of an urban sewer rat. The people of Saigon eat, sleep, do deals and pray in these narrow alleys. They probably fornicate, give birth and die in them too – most likely run over by one of the many motorbikes that race through them, for they are popular rat runs. And runs for those real rats too, of which we’ve seen plenty – fat, bold, happy brown rats who are not afraid (for they are tolerated by everybody and there is no such thing as pest control) to scamper about day or night feeding on the plentiful discarded food.

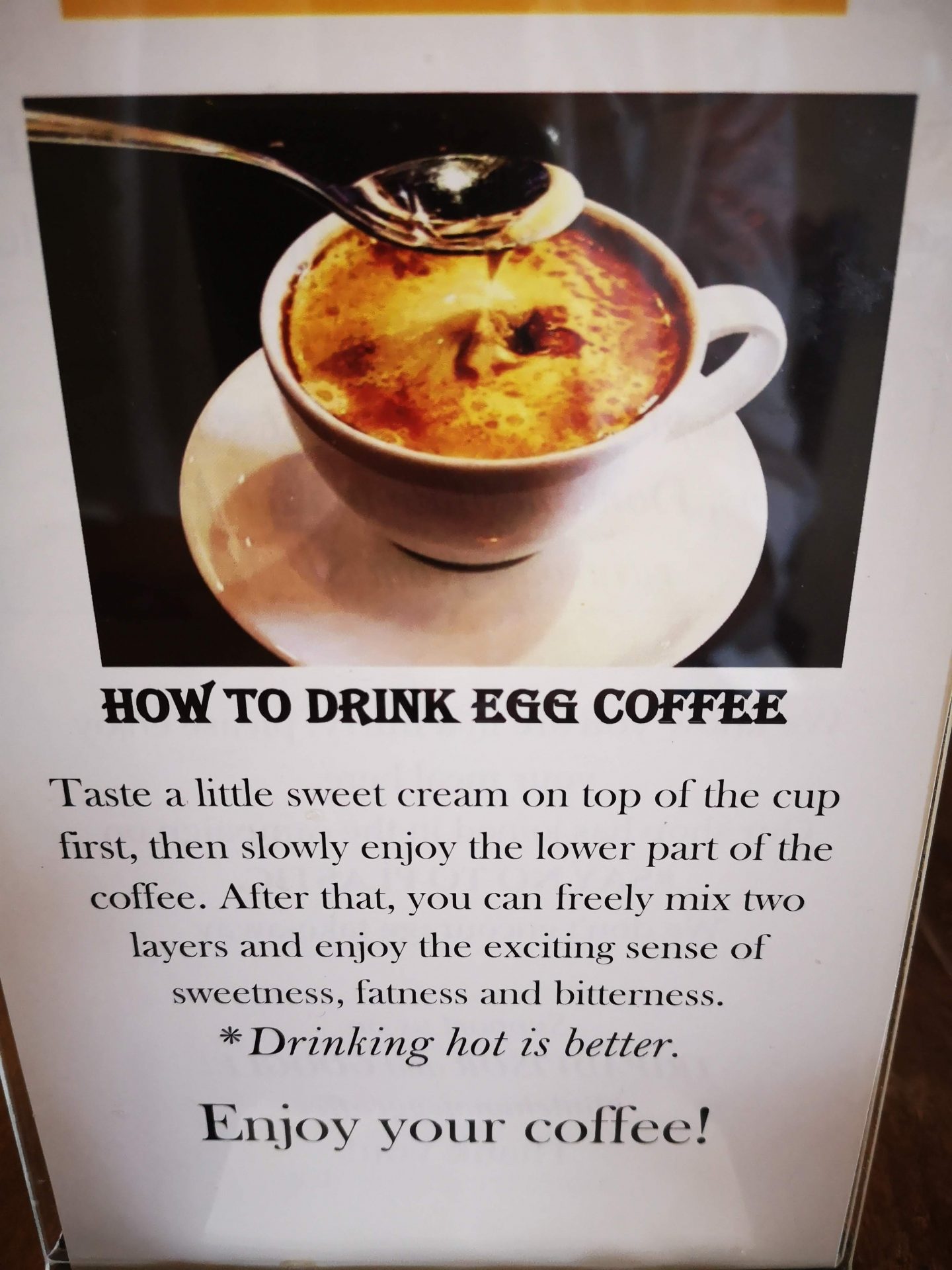

On the top floor of a nondescript building with an entrance almost blocked with forgotten furniture is a cafe called Little Hanoi, which serves something called egg coffee, an invention of the North during the years of war and deprivation. It’s excellent Vietnamese coffee with whisked egg yolk instead of milk. It sounds weird but it’s delicious. And they also do the best eggs and avocado on dark bread. We have breakfast here every morning for three days. The walls of the cafe are covered with some wonderful photographs, one of which is an enlarged portrait photo of Ho Chi Minh as a young man. It’s not an image of the Uncle Ho we all know – grey haired with the Sino goatee beard. This young man is clean shaven, he looks a bit uncomfortable in a white shirt and undone black tie. He has the most incredible eyes – dark, moist and dreamy.

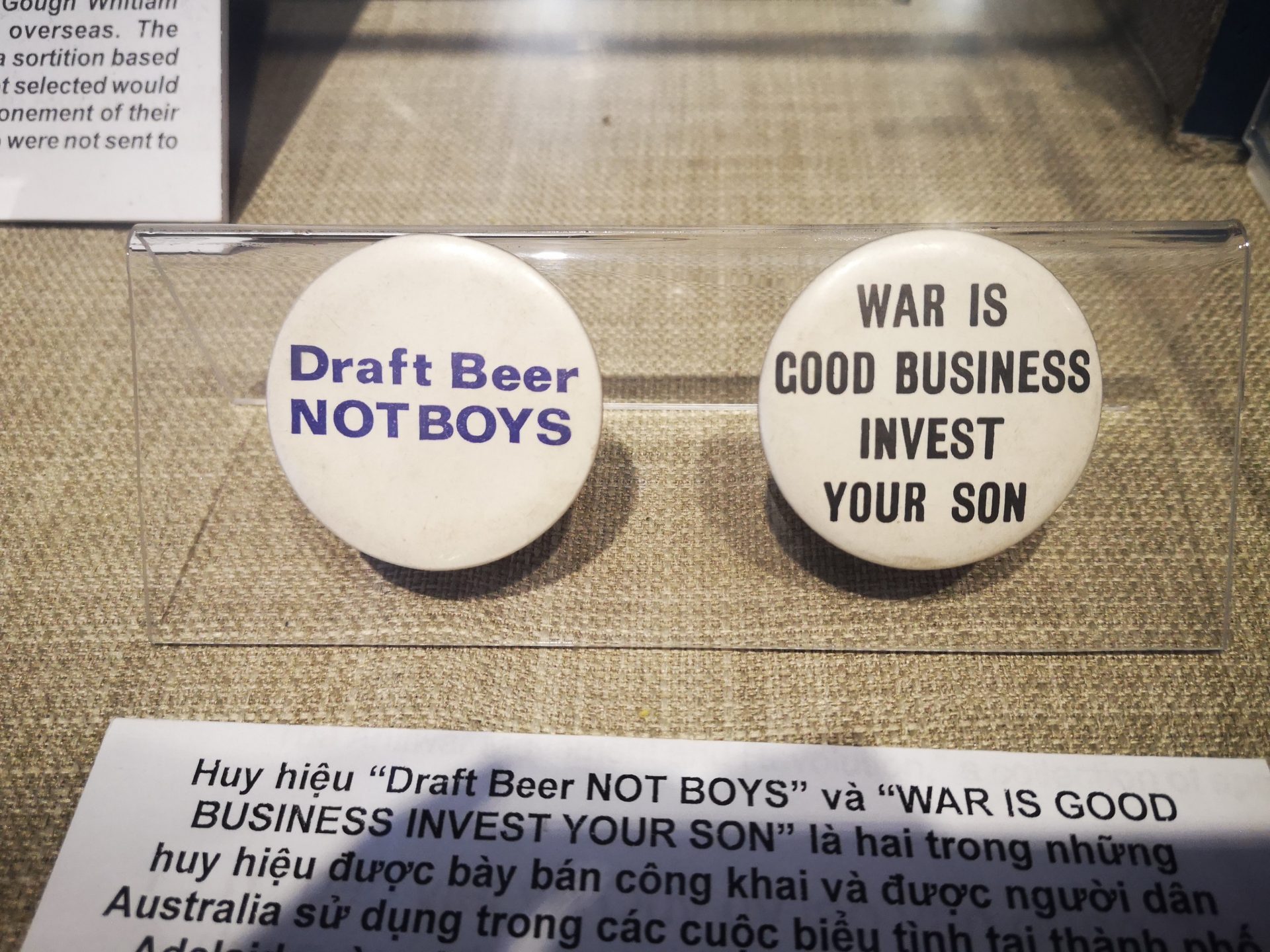

Our first destination on day one is the War Remnants Museum – the Vietnamese perspective on the war with the USA. There’s a US Chinook helicopter parked outside, and a Huey helicopter gunship with a belt fed rotating barrel machine gun mounted inside the cabin which has its doors off. It’s quite something to see these familiar aircraft up close. Were these aircraft hastily abandoned or captured? Nobody seems to know. The ground floor of the museum is dedicated to the world’s protests against America’s war in the region. There’s a very good presentation of the historical events and another of the horrific technology employed by the US including the dreadful and ongoing effects of Agent Orange defoliant – the descendants of those exposed to the chemical continue to be born with terrible deformities.

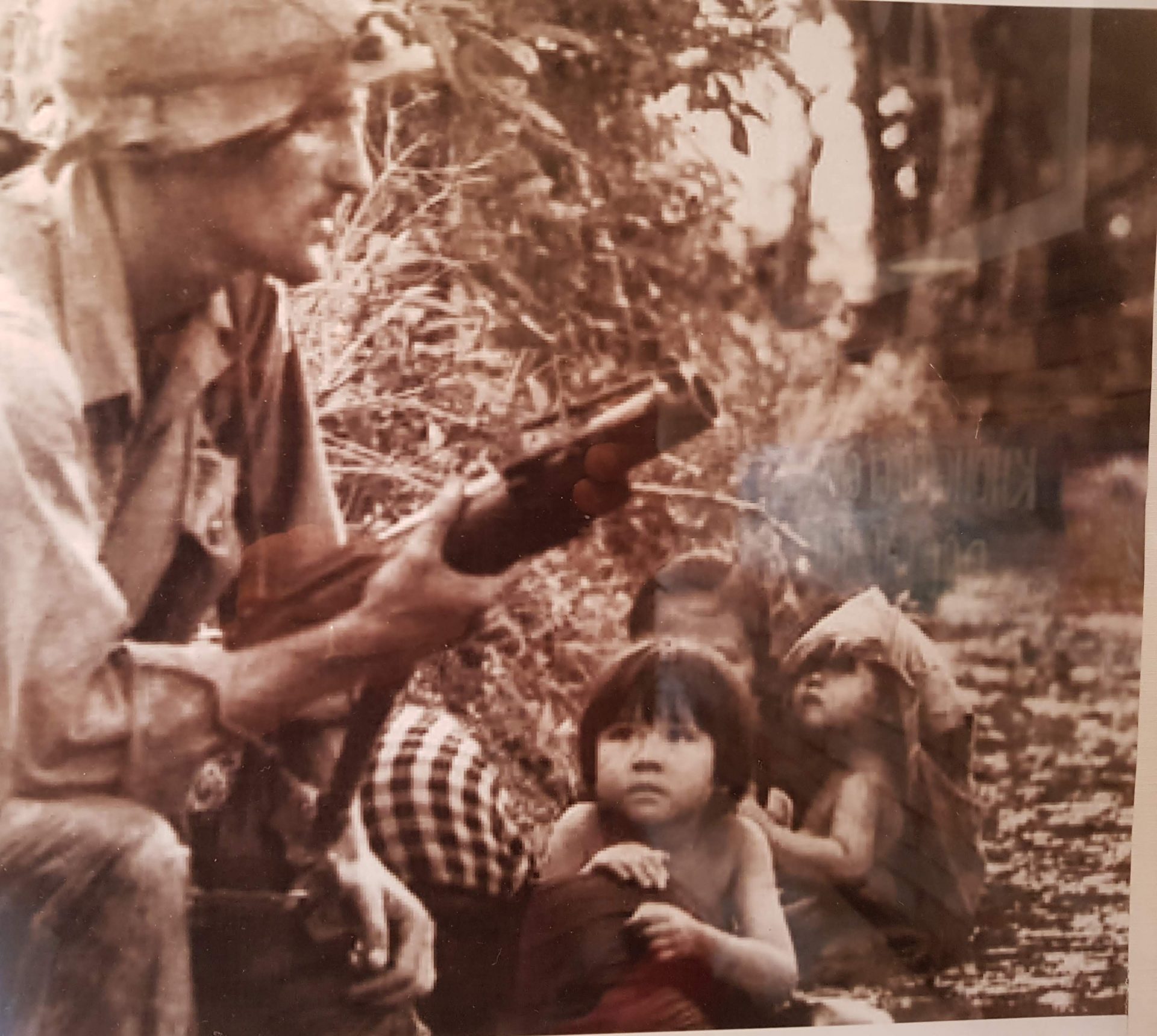

But for me the most moving and impressive, is the exhibition of war photography on the top floor. The Vietnam war was probably the last one where journalists were allowed free reign, within practical limitations, to cover events as they saw fit. Talented and courageous men and women journalists of many nationalities were killed whilst writing about and photographing the conflict. And it was this reportage that turned global public opinion against the US and may even ultimately have had an effect on the war’s outcome. I know of many of these photographers and I’ve seen a lot of these images before – but there are so many more, both photographers and photographs that I’ve never seen. It’s a remarkable exhibition.

Some might call it provenance. I’m inclined towards calling it a bizarre coincidence. Back in early December, before anybody had heard of Coronavirus, I picked up a book called The Ringway Virus by the Australian author Russell Foreman. The book opens with an aircraft crash in the remote jungle of Papua New Guinea. Two passengers survive, a young Englishwoman and an American guy. They are rescued and cared for by an isolated tribe who have never before seen a white person. The novel then takes us to Australia where the daughter of a couple from London on an extended vacation, contracts a flu virus from which she ultimately dies, but not before passing on her deadly contagion to her parents and those she encounters. The virus is a highly contagious killer that threatens the very existence of humanity on earth. The only likely survivors are the couple and their tribal hosts in the rainforest. As I say, encountering this book purely by chance was a strange coincidence but prescient too.

Vietnam is not relaxed about the global Coronavirus epidemic. Immigration has my phone number and I get regular messages informing me about prevention and symptoms. Posters and big screens display similar messages. Our temperatures are taken at public places and there are alcohol handwash bottles all over the place. Hotels won’t take guests from stricken regions and some aircraft from those places are being turned back. Saigon is not the overwhelming mass of humanity I was expecting.

It’s lunchtime and hotting up so time for air-con and a drink. There are three grand hotels in Saigon: The Caravelle, The Rex and The Continental, and they’re all worth visiting for some historical or literary connection. The war journalist John Swain in his wonderful book River of Time says this about the Continental in the early 1970s, “It was impossible not to like the Continental, with its green shutters, gently rotating ceiling fans, it’s shabby romantic air and its staff who always seemed to be sleeping on mats in the long corridors. We basked in the fantasy that Graham Greene had written The Quiet American there”. But the grand old colonial bars of these hotels have been unsympathetically refurbished and the charm has gone so we abandon the idea of a cool drink and walk for half an hour to find the monument dedicated to Thich Quang Duc.

In June 1963, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Quang Duc, in protest against the discrimination of Buddhists by the Vietnamese government, burned himself to death with petrol at a busy intersection in Saigon. Associated Press photographer Malcolm Browne had been informed that something was going to happen at the scene that day, and the stark black and white photograph he took became a shocking and famous image of the turbulent 1960s. It’s an image I know well. See Thích Quang Duc

US journalist David Halberstam was also present and he said, “‘…….. I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered to even think … As he burned he never moved a muscle, never uttered a sound, his outward composure in sharp contrast to the wailing people around him.” Set back from the very intersection where his immolation took place is a beautiful bronze statue of Thích Quang Duc enveloped in stylised bronze flames. Despite its proximity to the road, it’s calm here and we sit, contemplate and rest for a while.

The Ambassador car in the above image is the actual vehicle that was used to drive Thich Quang Duc to his death. It’s parked in a garage behind a pagoda in Hue city in central Vietnam.

Our second day is dedicated to the quest of food and Jo has an itinerary of restaurants where we will eat Vietnamese specialities including snails. Stupidly I’m wearing flip-flops and we will walk miles today. The pavements in Indochina are fragmented obstacle courses, full of holes and obstructed by concrete slabs, twisted metal, cars, motorbikes and discarded trash. They’re not ideal for flip-flops. In the late afternoon we arrive at District 4. Jo has written a blog to cover this foodie outing. My only contribution is to let you know that eating a snail is a bit like chewing a condom (I can only imagine).

On our way to District 4, I literally stumble, in my flip-flops, across a street of antique and bric-a-brac shops. The first shop on the left has, in a glass display counter, a tray of writing pens in which I spot a black Parker 50 (1950 vintage fountain pen). The Parker 50 is a lovely pen to write with and it’s quite collectable. I ask the stern young man in charge if I may take a look. It’s in fine condition. How much? I ask. Eighty dollar he says. A tad too much I think. We are a bit short on ready cash, I don’t start to haggle and he swiftly puts it back on display. If you’re ever in District 4 in Saigon and it’s still there, do try and get it for $20 to $30. That’s a deal.

Wherever you are in downtown Saigon, its tallest building, the Bitexco Financial Tower, by the river, dominates the skyline. It’s 68 floors high and abutting the 51st floor is a semi circular helicopter pad. Jo has discovered (or knows intuitively) that there’s a bar overlooking the helipad. And by pure chance we’re heading that way in a taxi just before sunset. Soon we’re at a window seat next to the helipad drinking B52 cocktails in the tangerine glow of a Saigon sunset. B52s in Vietnam. I’m sorry but that’s just a little bit spooky.

Please update more frequently because I truly enjoy your blog

web page. Thanks!

excellent as well as impressive blog site.

I truly want to thank you, for providing us far better details.

fantastic and remarkable blog site. I actually want

to thank you, for providing us far better info.