Our minibus driver wins second prize in the Indochina bonkers driver competition. He is permanently overtaking and consequently on the wrong side of the road for 40% of the drive playing chicken with oncoming vehicles. First prize goes to a recent taxi driver who was also only happy facing oncoming vehicles whilst simultaneously having two conversations on two mobile phones, one propped against his right ear and he other held in his left hand.

The approach to Phnom Penh from the east is through a vast construction site of shopping malls, hotels, apartment blocks and warehouses, all connected by new roads. It looks like a wealthy burgeoning metropolis and I’m wondering what underpins it all.

The city has a reputation for noise, pollution, dirt and overcrowding so Jo has been busy looking for an oasis hotel into which we can occasionally escape from the chaos. This proved to be a challenge but she succeeded with Hotel 252 which is set back from the road and separated from it by a big swimming pool surrounded by tropical fruit trees.

I’ve been thinking about the odours of urban Indochina. Diesel fumes, stagnant water and drains predominate. These are interspersed with the smell of dead animals and overripe fruit. Then there’s dust (which does have a smell) and smoke from burning rubbish and cooking oil (unpleasant) and smoke from burning BBQ meat, wood, charcoal (pleasant). The occasional waft of urine gets a look in as well. I never smell people as their personal hygiene is very good. There’s the delightful sweet smell of frangipani when one is fortunate enough to be in a garden, or on an avenue of frangipani trees. And finally there’s the pleasure of incense at formal and informal Buddhist shrines.

We plan to be in Phnom Penh for only two nights but we’ll extend that to three. As in Laos there is a discernible French colonial influence but perhaps not so prevalent, Cambodia’s past having been clouded by its more recent history.

We shall need something to lighten our mood this evening because today we shall visit the Choeung Ek Genocide centre; the Phnom Penh Killing Fields, and the Tuol Sleng Genocide (also known as S-21) Museum. This is not the place to chronicle these places in any detail but I would like to describe what they are and share with you some of my feelings about them.

After the Holocaust in Europe during the 1930s and 40s the world declared that such a calamity must never happen again. Yet from 1975 to 1978, an estimated 2.5 to 3 million men, women and children (lots of women and children) were tortured, bludgeoned and hacked to death, or left to die of disease and starvation. And all of this was perpetrated by their fellow Cambodians. What madness caused this? History focuses on one man Pol Pot, a failed radio mechanic, who learnt his twisted Communist ideology in Paris (shades of the French Revolution and the Terror) and honed it under the tutelage of China’s Mau Zedong.

Impoverished, damaged, post Vietnam war, Cambodia was ripe for the deranged undertaking that reduced the country to a condition of pre-civilization. Pol Pot inherited and enlarged an army of young toughs, who, with indoctrination and promises of riches, power or just a day’s pay he began dismantling the nation; the calendar was set to year zero (a definite French influence), the name of the country was changed to Democratic Kampuchea (any country that has the word democratic in its name never is democratic) and the following was abolished: family, commerce, currency, ownership of property and possessions, clothing styles, education, religion, mail, radio, TV, newspapers. The ideology called for a complete break with the past and unquestioning loyalty to the party, Angkar. Any intellectual, ie anybody that could read and write, was, to use the regimes expression, crushed, killed, together with their families. Subsequently, the regimes paranoia and blood lust sought victims without logic, all that was required was a “confession” elicited through torture.

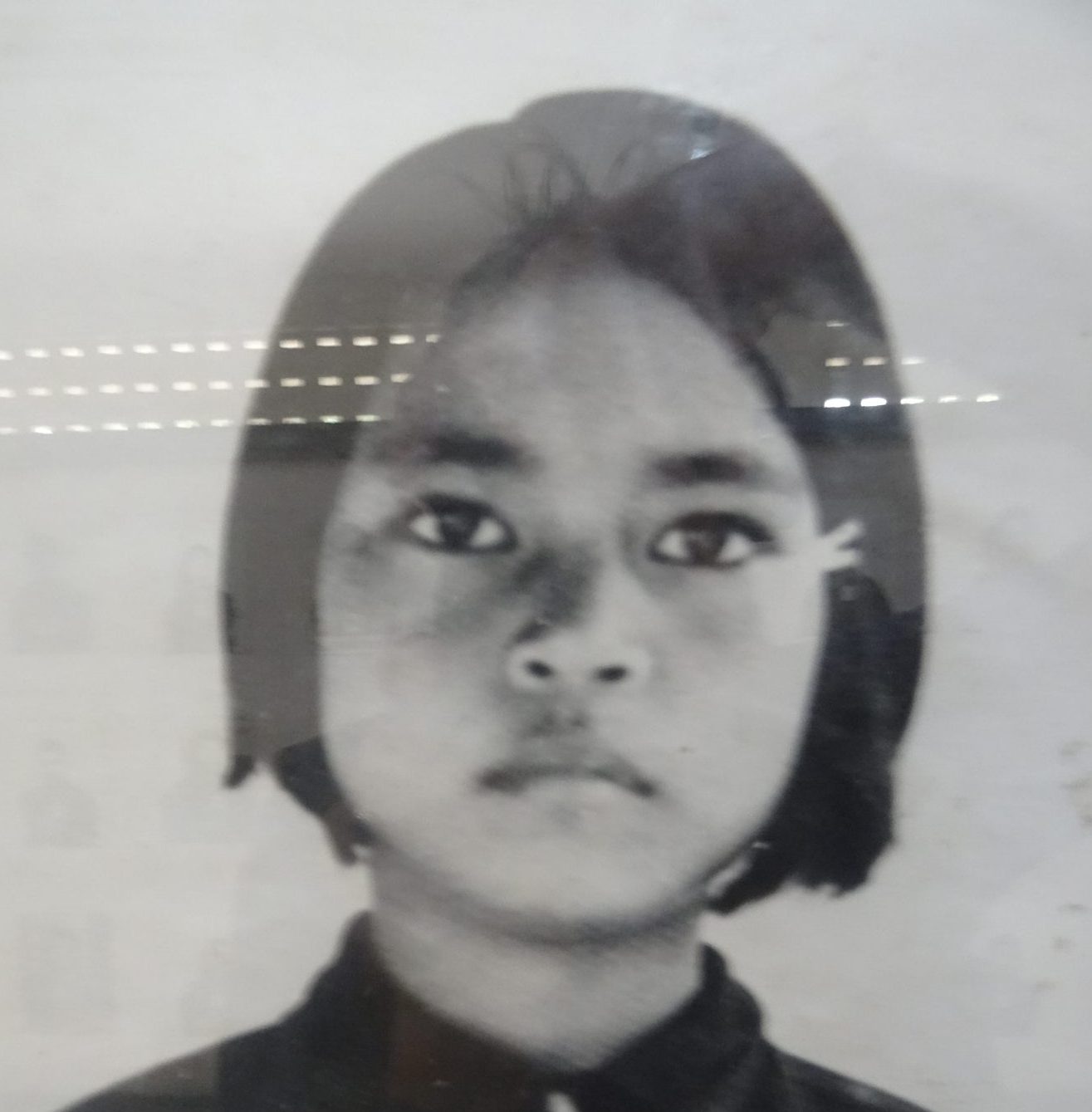

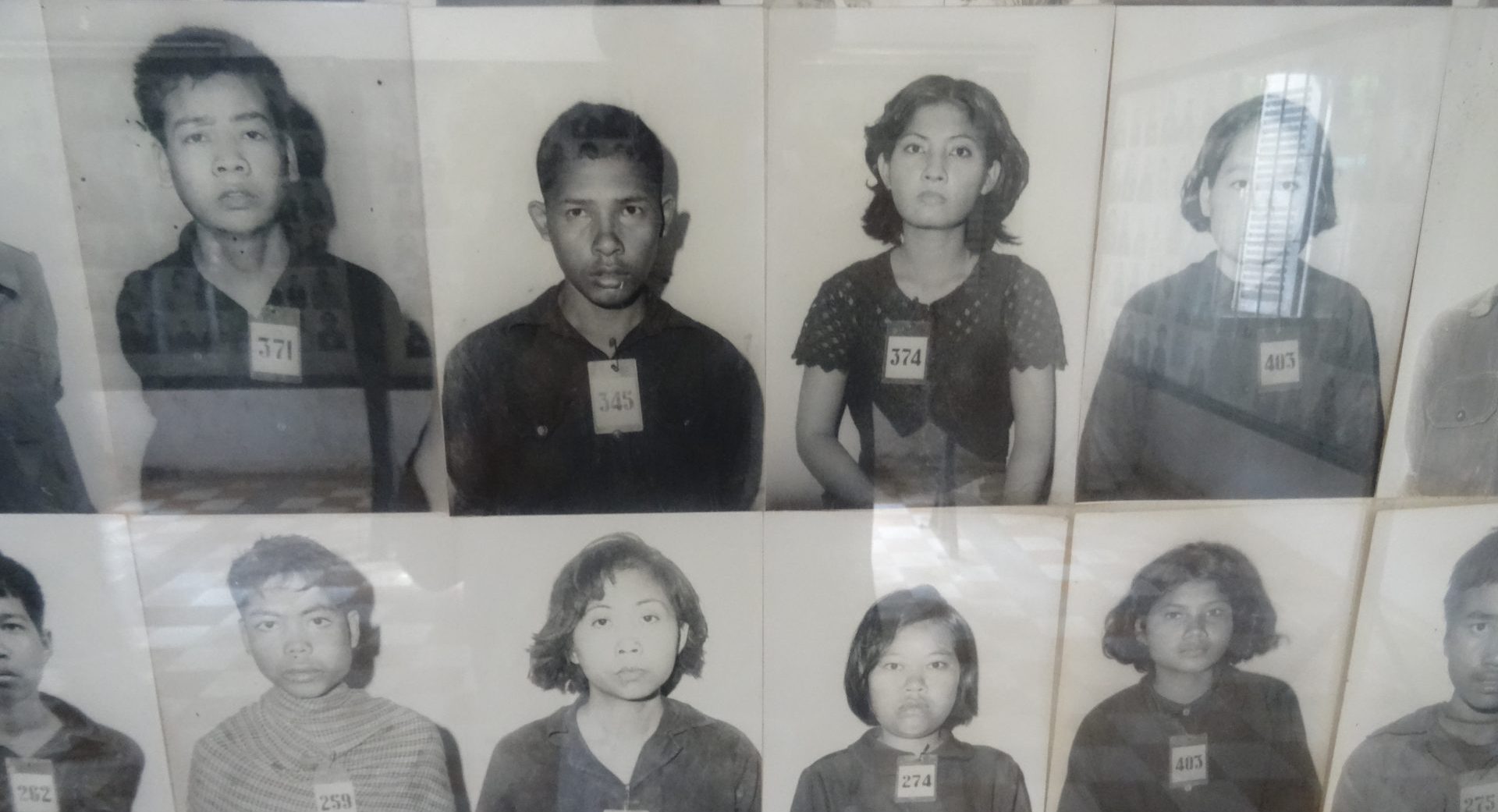

S-21 in Phnomh Penh, once a small secondary school, became one of the 300 interrogation and torture centres in Cambodia. And it is without doubt one of the most harrowing and ultimately depressing places I’ve ever seen. It’s too awful to describe in this blog what was done to people in here. Killing in S-21 was considered a mistake. Inmates were to be tortured, sometimes for months, to get a confession, then trucked out to the local Killing Field to be hacked to death. Up to 20,000 we’re processed in this torture centre and there were only 12 confirmed survivors. There are black and white mugshots of many of the victims displayed in one of the classrooms. Those of the women and children are particularly disturbing – as you’d expect they look like so many of the ordinary innocent people you’d see on the streets of Phnom Penh today.

Of the millions murdered, there were but a handful of westerners. In my twenties I’d read a news report of the fate of three of them. It’s a story that haunted me at the time, one I’d forgotten, only to be reminded of it at S-21 today. In August 1978 three young guys, New Zealander Kerry Hamill, Canadian Stuart Glass and British John Dewhirst, were on the adventure of a lifetime, sailing Kerry’s yacht Foxy Lady into the Gulf of Thailand from Malaysia. They were heading for Thailand but – some say as the result of a storm – they found themselves near Koh Tang island in Cambodian waters where they were intercepted by Khmer patrol boats. They were so tragically unfortunate as they were but a few miles from the Thai border. Glass was killed during the initial encounter, while John Dewhirst and Kerry Hamill were captured, blindfolded, taken to shore and trucked for nine hours to Phnom Penh. Both were executed after having been tortured for several months at S-21. Witnesses reported that a foreigner was burned alive; initially, it was suggested that this might have been John Dewhirst, but a survivor would later identify Kerry Hamill as the victim of this particular act of brutality. Robert Hamill, his brother, and a champion Atlantic rower, would years later make a documentary “Brother number one” about his brother’s incarceration and execution.

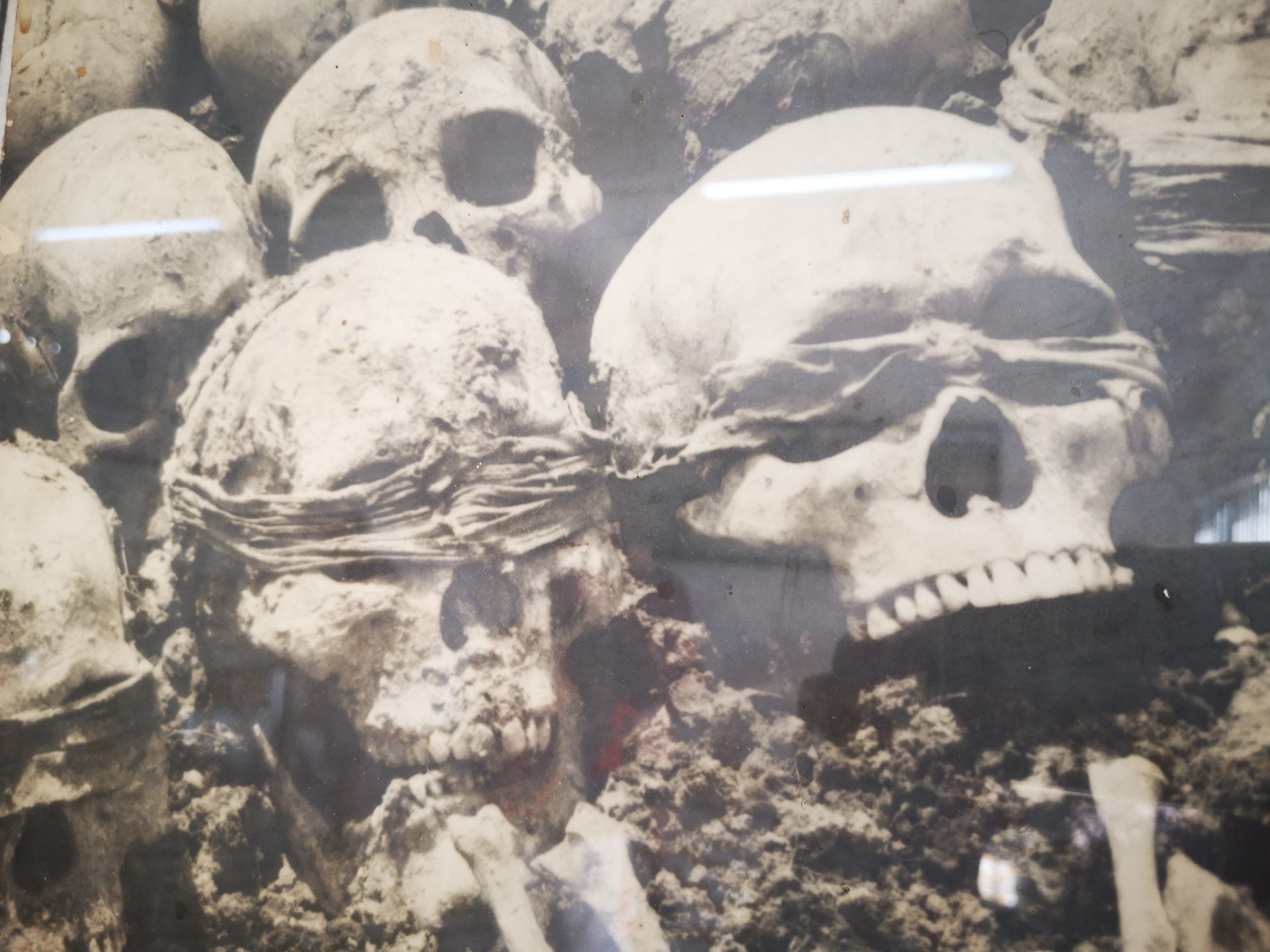

Both museums are excellent portrayals of the time and place, the audio accompaniment being particularly thoughtful and sensitive. But there are ghoulish, and I think disrespectful, skulls and skeletal remains of the dead at both S-21 and the Killing Fields museum. It is Buddhist practice to dispose of human remains so that the soul can be released from its physical form. This is not my belief but it is that of most Cambodians. Some consideration should surely be shown to these tragic victims and their families.

In 1978, to put a stop to bloody cross border raids into their country, Vietnam invaded Cambodia and halted and exposed the horror of what had been happening. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge fled west to the Thai border where they remained, bizarrely recognised as the legitimate government of the country by the West, until 1998 when they were offered a deal which basically said, lay down your guns and you’ll not be held to account for what happened.

Almost a quarter of the population had been murdered, the country was in ruins and an entire generation of people traumatized. And the final indignity is that only three people have been tried, found guilty and sentenced for genocide. Tens of thousands of Khmer Rouge soldiers walked free. It’s a nightmare. About 60% of today’s Cambodian population is under 25. Till 2009 it was not mandatory to teach them about the Khmer Rouge. Is Cambodia’s reconciliation collective amnesia? The people are definitely ambivalent (or afraid) about reopening old wounds and they’re reluctant to speak about politically sensitive issues in a country where political views come with a price (one of our most charming and generous hosts in Cambodia had just spent six months in prison for political dissent).

How does anybody between the ages of fifty and seventy, the generation of the genocide, cope with the psychological scars? Karma may offer one possible explanation. According to anthropologist Fabienne Luco, who has been working in the country for about 20 years, the concepts of sin and guilt do not exist in Cambodian society.

“It is the notion of karma that holds sway”, she says. “When you do something bad or good, you are responsible. Bad things will follow you in your next life. That’s why people are not so interested in what’s going on at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal [the United Nations backed court that is currently trying the senior leaders of the regime]. It’s not human beings who will punish the perpetrators. They will be punished in their next life.”

She continues, “I don’t believe that former cadres consider they have been doing bad things. I have interviewed so many of them – the notion of guilt doesn’t exist. They say, ‘I was obeying orders,’ ‘I was a perfect civil servant,’ ‘It’s not me, it’s the one who ordered me to do it.’”

My own final thought on this is that the horrors of its recent history is in stark contrast to the beauty of the country and the overwhelming friendliness of the people we meet.

Enough! Back to the present. It’s been a harrowing day so we want to eat somewhere delightful this evening and can’t resist the allure of Armand’s Bistro, located on a street just up from the riverside near the night market. We decide to walk and as the street becomes darker and more remote, Jo declares that the Bistro can’t possibly be up here, away from the riverside district of bars and restaurants. But I see a golden glow of lights up ahead on the left and there it is, my Bistro! And it’ a small cosy restaurant, a touch of 1930s Paris with warm lighting, a lovely bar, linen tablecloths, a smell of fine cigars and some interesting clientele; a rotund Englishman in a white shirt and red braces is at table entertaining a small group of locals including a grey haired, pencil moustachioed Khymer chap in a three piece black pinstripe suit with a white silk handkerchief in his breast pocket. They’re both pulling on big Havana cigars. The Englishman’s lifesize portrait hangs above the bar.

I acknowledge the smile of a man standing at the bar as we are shown to a table and offered the wine menu. Blackboards on the walls present the a la carte menu which is French cuisine at UK prices. We order a couple of large glasses of Cahors red wine and exchange a few quiet words about how we might decently enjoy something to eat without busting our meagre budget. French bread and butter arrives but Jo won’t let me touch it as we may just drink the wine and leave. A sign above the bar declares that a bottle of 2007 Château Mouton Rothschild is available for $1,070 but more encouragingly a dozen oysters will only cost $18. I inquire as to where the oysters come from: Vietnam, which isn’t that far away so they should be ok. But I’m informed that they’ve sold out.

The man who caught my eye at the bar approaches our table and introduces himself. He is the co-owner, un homme tres particulier, un vrai gentilhomme. We all exchange the usual niceties and then spend the next two hours in his charming company drinking red wine, finer than the Cahors, with the restaurant’s own pate de fois gras – and I get to eat the French bread with delicious creamy salty butter. The co-owner’s name is Bauduin Parmentier, he’s a French Belgian named after Bauduin, who became king of the Belgians in the same year Bauduin was born; 1951. He has owned various businesses in France including a vineyard and a Michelin starred restaurant but found it impossible to effectively run a business under the stranglehold of French bureaucracy so moved to Cambodia where he half owns this place (with me!!), a cafe in Siem Reap and an Italian leather goods shop in Phnom Penh. He clearly loves the life in Cambodia; his face lights up as he talks about the vivacity, idiosyncrasy and charm of the people ‘if zey ave ze money zey will eat all the time and zey will sleep anywhere anytime’. And it’s so true, food is always being consumed and you see people fast asleep in the most unimaginable places. He talks of the paradox of the Khmer’s cheerful disposition and their unpredictable rise to anger and aggression. He tells us about the enormous wealth of the elite, of the corruption, the greed and the wanton destruction of the country’s natural resources. At one point in the evening he and I become momentarily maudlin, a little depressed about the future, and not just about Cambodia, that Jo chastises us ‘Come on boys, do cheer up, we’re alive, we’re happy and in such lovely company’. The moment passes!

It’s midnight (we haven’t seen midnight since our last trip on an overnight bus), the budget has gone to pot but we agree to return the next night for some Vietnamese oysters. Bauduin says that as it’s half my Bistro I must come back tomorrow.

The next day is spent by hotel pool reading and writing. This evening we return to Armand’s Bistro for those oysters and a bottle of ice cold Sauvignon Blanc. It’s a culinary delight, comfort food and drink, as tomorrow we’ll be living in a hut in the Cardamom mountains. The Cambodian food is ok, not brilliant, we enjoy it, but rice or noodles with fish or chicken, however delightfully spiced, garnished and prepared is not something we are used to three times a day. We enjoy a couple of cognacs with Bauduin at the bar before we leave. Perhaps we’ll meet again, in his cafe in Siem Reap, in a couple of weeks time.

excellent and fantastic blog. I truly wish to thank

you, for providing us much better info.

Hi Armand and Jo, I stumbled upon your blog whilst trying to find out about the swift nests (thanks Jo for answering that one) and have been reading all Cambodia posts avidly. We too are a mature couple on a shoestring, currently cycling in Cambodia and Asia for a year. Armand, thank you for the post about Kerry. We are good friends of Rob Hamill and know well the ripple of devastation Kerry’s death had on his family. Thank you for writing so sensitively about this personal tragedy.