We are travelling in our Ford Transit Custom campervan from the Yorkshire Dales, northern England to the southern Mediterranean coast of Turkey – a round trip that will cover over 8,000 miles in eleven weeks. Our outbound journey to Turkey will take us through France, Germany, the Czech republic. Austria, the Balkan states of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Serbia, and finally Bulgaria. We’re in no rush and circumstances will slow us down. It will take five weeks to reach the Bulgaria Turkey border.

It’s very difficult to visit the Balkans without encountering reminders of the bloody civil war when, in the 1990s, the federation of Yugoslavia tore itself to pieces. After more than twenty years since the end of that war, those stark reminders are everywhere; in encounters with the people, in the bomb shattered and bullet pockmarked buildings, in the still landmine contaminated landscape and from the memorials and museums. Whilst that may seem somewhat grim, the Balkans is a beautiful region of southeastern Europe: Croatia’s long Adriatic coast of beaches and islands, Slovenia’s lakes and alpine mountains, Bosnia and Serbia’s mountains, gorges and river valleys are magnificent. The people are friendly and engaging. And the food and drink is delicious – and great value.

My companion in the Balkans (other, of course, than the ever enthusiastic and patient Jo) is the cyclist and travel writer, Dervla Murphy. Dervla was born in County Waterford, Ireland in 1931. In 1999 and 2000, when in her sixties she undertook two long distance bicycle journeys through devastated Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Albania, Montenegro and Kosovo. She died aged ninety, three months before we set out on this trip to Turkey.

I have with me her 2003 book: Through the Embers of Chaos. Balkan Journeys, in which she recounts her cycling journeys, describes the history and politics of the region, and her encounters with the people and the landscape.- and the dogs for which she had a soft spot. What comes across in this book is Dervla’s sharp intelligence, her courage, enthusiasm, stamina and powers of inquisitiveness and observation. But perhaps above all, her Irish gift for engaging with people and encouraging them to give of themselves and their experiences.

Into Slovenia

On the afternoon of 26th August, we cross from the Czech republic into the small Alpine country of Slovenia. The border region is one of easy rolling hills and vast swathes of well shorn grass. It is very hot. We have a load of Czech cash that we should have spent on diesel fuel before entering Slovenia but we took a minor road without encountering a gas station. So we map out a major road and drive for 45 minutes back to the Czech Slovenia border to buy fuel – a frustrating introduction to the country. It’s 30°C and 6pm before we climb a steep narrow winding track to a small plateau with a magnificent view of grapevines on the hills below. We cook up spaghetti carbonara and spend the night here.

The next morning it’s still very hot. There’s a formidable wooden watchtower above us which Jo climbs. She says the views are fantastic and encourages me to go up it too. I’m standing below it looking up. The broad stairwell rises inside the open framework. I climb. I have graphic dreams where I experience realistic vertigo. This is no dream. Half way up I look down and slightly sway. I climb. At the top is an open platform surrounded by a waist high railing. The health is here but where’s the safety? One of the less pleasant features of vertigo is the compulsion to jump. I look down again and take a deep breath. I sway and quickly descend; each lower level is a relief. “Great view eh” says Jo. “Wonderful” I say, but I’ve already scrubbed it from my memory.

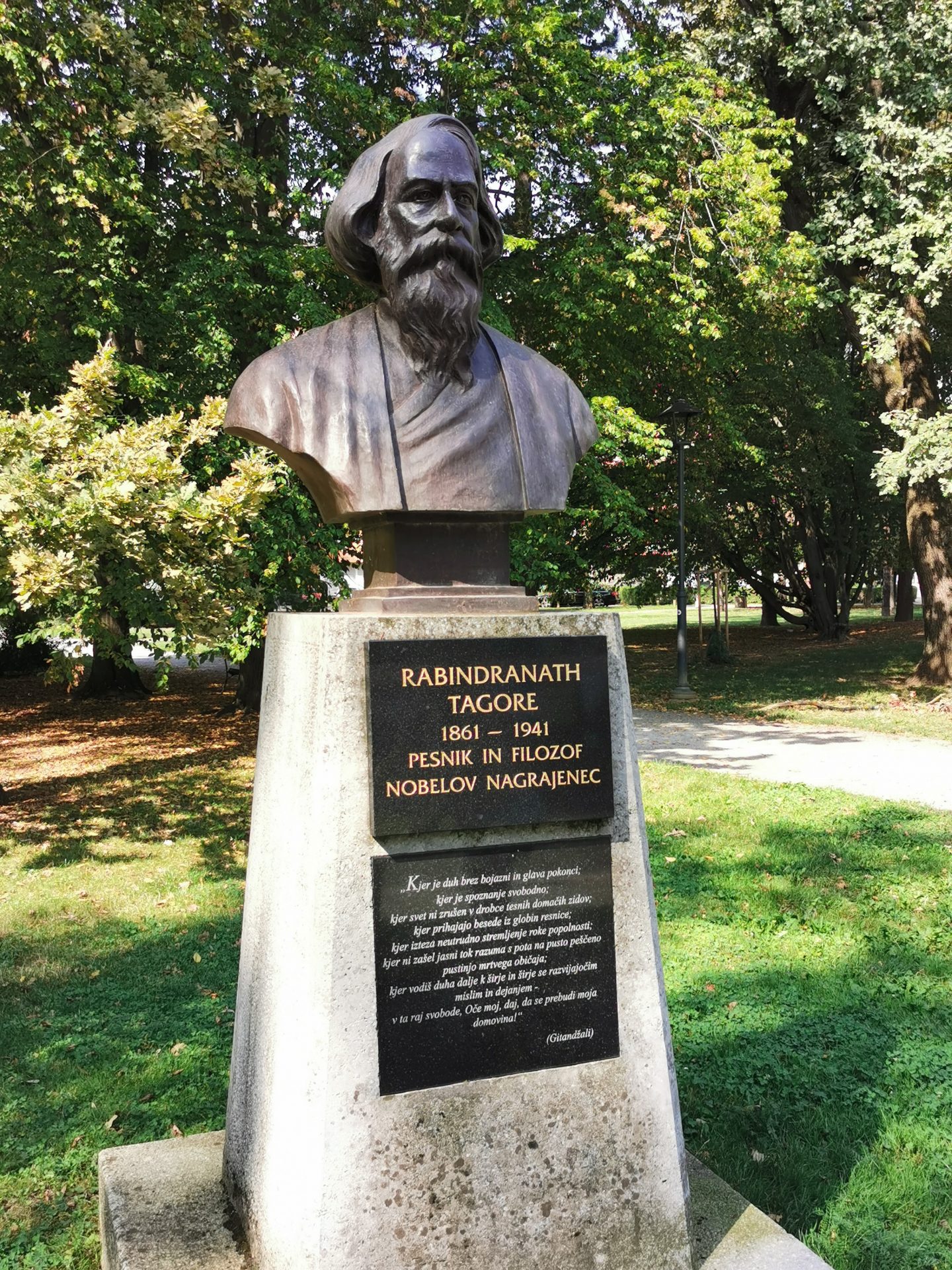

We visit the ancient towns of Maribor and Ptuj; both next to the wide Drava river. We cycle the Bromptons around Maribor’s broad, traffic free avenues and big bright squares. Jo wants to see the more than 400 year old Zametovka grapevine. I want a bottle of the local wine and a croissant. In a local park we find, to my surprise, a statue of the Bengali polymath (poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter) Rabindranath Tagore. Over the years I’ve bought and sold some fine editions of his books. The Slovenian poet Srecko Kosovel was considerably influenced by Tagore – an unexpected kinship of ideas and sentiments between this part of Eastern Europe and India. In the 1960s Tagore was on the Slovenian school literature curriculum.

You’d expect that travelling in a van, in summer, enchanted by the sublime landscape and ancient cities, eating local produce, drinking fine wines, and meeting the friendly locals would be a constant delight. But when you’re in a small campervan for months on end there can be tensions. The weather can be dismal, the landscape a flat, bleak urban or industrial wasteland, and you occasionally encounter miserable bastards. We sometimes want to do different things and can’t agree on a plan of action. We are irritable, tired, moody and find each other difficult and annoying. We get, as they say in Yorkshire, right pissed off. This isn’t the prevailing mood but it happens.

After some dispute we agree to drive on to the Jeruzalem wine region of Northeastern Slovenia. The countryside from Ormoz in the south to Jeruzalem is beautiful, with terraced vineyards and many vinotekas along the route for wine tasting. The wines are almost exclusively white, Pinot Grigios, Reilslings and a local grape variety, Sipon. We stop at a vinoteka, taste a few, and buy a Sipon. The viticulturist is chatty and tells us that the grape harvest is now a month earlier than in years past, at the end of August instead of the end of September. And over the last few years there’s been just a few days of snow in February when it used to snow all month. And this year, no rain in the crucial early months of May and June and too much in August. And wasps are ruining his grapes. The wine would be good this year but there will be less of it. Doom and gloom – the farmers’ lot.

But this is not the first time that a winegrower has mentioned climate changes. We heard this in Greece too. But is it a real problem or should the growers just adapt to normal climate changes without being so gloomy? Harvest a month early – surely not such a big deal. Jo says I’m a climate change denier which I deny. I’m a climate apocalypse denier.

Anyway, that aside, he’s a nice guy and recommends another vineyard close by where we can park for the night. So we drive on, past hillsides of vines heavy with black grapes, to another stunning hilltop location. But the owner wants 20 euros for the pitch – much more than we would normally pay. We don’t need water or electricity or food, so we’d just be paying for the view and toilet. And there’s a free car park nearby with quite a good view – so Jo’s not inclined to spend. We are at odds again. I like it here. I’m done with driving for the day and I have a glass of the vineyard’s Sipon in my hand. We stay but the mood is chilly. Overnight there’s a terrific thunderstorm after which we’re plagued by a pesky mosquito that evades all attempts to squash him. Finally, despite my protests, Jo sprays the cabin with insecticide and I’m forced to sleep outside on a damp recliner.

The following morning it’s cooler but still very hot in the sunshine. We have an unexpected change of plan. I have an infected molar tooth that has previously had a root canal treatment and a crown. A couple of weeks ago I had an abscess lanced by a German dentist. He prescribed antibiotics and advised me to get it fixed as soon as possible. A friend of Jo’s has recommended a dentist in Zagreb with whom I have an emergency appointment tomorrow. But first I need an x-ray which I’ll try to get today. I don’t feel good about this diversion but there’s nothing I could have done to predict it in England. Jo is quietly understanding, I think, or at least accepting of the problem.

It’s a boring, busy 2½ hour drive to Zagreb on one of those long bleak commercial highways that could be anywhere and everywhere; lined by car showrooms, shopping malls, drive-in fast food outlets (McDonalds – the burger bar that ate Europe) and industrial units. The dental x-ray shop is located in downtown Zagreb and we cruise around to find parking for the night.

The central district has some fine buildings but they are blighted by mindless graffiti. Some say the street art in Zagreb is a ‘must see’ but what we see is not the beautiful and stimulating modern street art or murals that can enliven an otherwise lacking urban scene. This is graffiti tagging – those formulaic bulbous letters making up, to the uninitiated, i.e. almost everybody, meaningless scrawl tags. And it’s everywhere, every historic apartment building or office block is covered in this stuff from head height down. Only the marble of the Sheraton Hotel remains unscathed. And Zagreb appears to have resigned itself to it – to be accepting of this ugly blight.

The place is a dirty vandalised mess. The streets are strewn with trash and you can taste the air pollution – in November 2021 Lahore, Pakistan was the most polluted city on earth, followed by Delhi, India. Zagreb was third. The approaches to the centre and downtown itself are congested with traffic and parked cars. We like to cycle into a city from a place outside the centre, but that would be dangerous here – there are no cycleways and the traffic is chaotic. It’s like London at its worst. In one potential overnight parking location there are cans, bottles, used food containers and dirty nappies strewn across the car park, and it stinks of urine. Something has happened to Zagreb. We’ve been here before and enjoyed it. But in just a few years the city has lost its civic pride. Covid will likely be blamed, but I suspect there’s more to it than that. For now, we sadly have to accept that we will not return in a hurry, or recommend the city as a destination to anyone else.The Zagreb authorities and its inhabitants need to get their act together.

We find a short term car park close to an instant x-ray place, the Multiray Centre. Multiray is brilliant. The technician speaks English well, and within twenty minutes I have two x-ray images of the offending tooth for just 9 euros.

We want a beer and walk across the central square to the old historic town, much of which is under scaffolding for renovation.On a pedestrian street of bars and restaurants, we try a Sri Lankan street food place and I enjoy an excellent kottu roti. Jo uses our contactless card to pay and gets overcharged almost double for a meal – 467 kuna instead of the actual bill of 267 kuna. We rarely check these types of payments, but she spotted this ‘error’ and was refunded with an apology. The experience has left an unpleasant feeling. Later we eventually find a tree lined avenue between the zoo and a football pitch. It’s quiet and after a good night’s sleep we enjoy an excellent early morning coffee in a pavilion restaurant in Maksimir park by the zoo – a peaceful oasis.

The dentist tells me that I need oral surgery. The tip of the tooth root is infected and the only way to access it is through an incision in the gum. The good news is her son is an oral surgeon. The bad news is that he can’t do it for a month. She prescribes more antibiotics and tells me that it will all be ok for at least another month and wishes me well. But I will soon discover that it won’t be well at all.

We’re happy to be leaving Zagreb and heading back to the southern forests of Slovenia where we stop at the splendid 13th century castle of Grad Otocec, now a Relais & Châteaux hotel, on a small island in the middle of the Krka river, accessed by a wooden bridge. There’s a big empty car park under trees on the banks of the Krka opposite the island. It’s a lovely place to spend the night. But it will transpire into what Jo will accurately describe as a complete f**k up.

We watch kingfishers darting along the river and in the evening eat a simple omelette with a bottle of Slovenian wine. We are asleep soon after dusk.

It’s the last day of August. It was my responsibility to ensure that we have the proper motor insurance cover for this trip and I assured Jo that we did. In the past we’ve had a Green Card document that stipulated the European countries for which we have insurance cover. Green Cards are no longer issued and my mistake was to assume that the same cover applies as stated on that old Green Card. But I woke up this morning with some doubts. I read the Insurance documents and other than cover for countries of the European Union I can’t find any evidence that we’re covered for Serbia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Kosovo or Montenegro. I know we’re not covered for Turkey but I can buy insurance at the border.

Jo is rightly pissed off. ‘This was your responsibility. I can’t trust you to even sort out the insurance’. I spend the morning on the phone to our Insurance Brokers who in turn speak with our insurers. Eventually I get an emailed document that itemises every country in Europe for which we have cover. But that list excludes Kosovo and Montenegro so we have to rethink our route. The problem is resolved but I’m feeling pretty incompetent.

In glum silence we go through the routine of preparing to move on. Then Jo asks me ‘where is my backpack?’ ‘I dunno, in the front I guess’. ‘It’s not there’ she says, ‘I left it on the driver’s seat’. ‘It must be there’ I say. ‘It’s gone’ she says, ‘It’s been stolen’. ‘I don’t believe it’, I say, ‘I locked the doors’ ‘Yeah you said you locked the doors but you didn’t did you?’

If Jo was writing this page it would be splattered with expletives. Trust, reliability, competence are all brought into question. Jo feels really let down by me and very uncomfortable about the fact that a thief had entered the van with us in it. I’m way too casual about security and am always brushing off Jo’s questions for reassurances about locking up.

Jo tells me that she had a strange feeling in the night that she heard the front door close but, as I’d assured her that I’d locked the door before bed, she let it pass as a dream. A campervan is always a target and, if you’re audacious, an unlocked one, even with occupants asleep inside, is easy pickings. The new backpack contained an old iphone and the spare keys to the van, plus another key, the absence of which will cause some anxiety in a couple of weeks’ time. We wander up the road to find the less valuable contents – tissues, snacks – discarded at the side of the road.

An unplanned journey for my damned tooth, inadequate insurance for our trip and now this. I have seriously f**ked up and will have my work cut out to vindicate myself from the charge of uselessness.

Jo is in no mood to “get over it” and we sit almost in silence as we drive. At about 2pm, we are at Baza 20 in the Kočevski Rog forest and stop for lunch. I apologise to Jo for being such an ass. I tell her I feel shitty about today and my previous responses when she checks up on locking. I’ll buy her a new backpack and start a new routine where we will deadlock all the doors except the side one at night. And I’ll make a point of saying doors locked when I lock up with the electronic key fob. Jo says thanks and we move on.

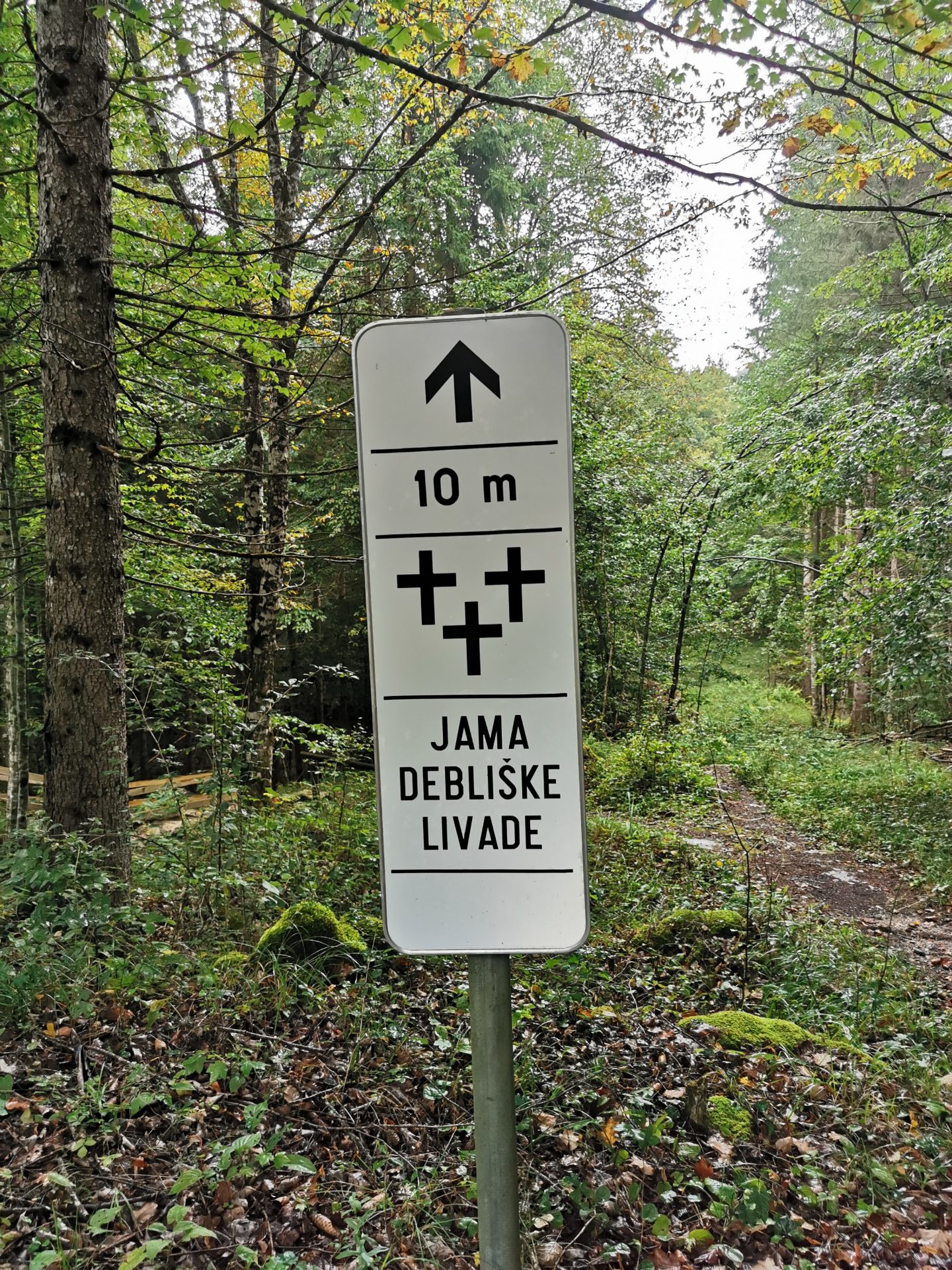

The weather has turned suitably grey. Baza 20 was one of the numerous camps in the woods of Kočevski Rog which were once the command centre of the National Liberation Movement of Slovenia in the Second World War. Brown bears allegedly live in this forest but the ticks are more prolific, less inhibited and potentially more dangerous, so we cover up and explore. We visit one of the bunkers and the sites of several mass graves. These burial sites are all over the forest and are the result of extrajudicial killings during and after the Second World War. Nearly 600 such sites have been registered by the Commission on Concealed Mass Graves in Slovenia, containing the remains of up to 100,000 victims. The postwar graves contain the remains of suspected collaborators, soldiers, and civilians that fled towards Austria in the hope of surrendering to the Allies (including the British army) in May and June 1945, as well as groups targeted because of their ethnicity (e.g. Gottschee Germans, Hungarians, and Italians) and civilians that were the victims of political purges or marked as “class enemies” to eliminate potential opponents to the new communist regime in Yugoslavia.

Britain’s involvement in some of these murders is tragic. After 8 May 1945 thousands of Chetnik (German collaborators) and refugees were sent back to Yugoslavia by the British army to be slaughtered on arrival by Tito’s Yugoslavian partisans. Nigel Nicolson, an Intelligence Officer with 5 Corps of the Eighth Army, later gave evidence:

We were ordered to tell these wretched men that they were going to Italy and that they would remain in British hands. And this was something that even at the time shocked us deeply. We had to put up a sort of facade. They were collected at this railway station. It took several days actually. These long, long trains with box cars and we used to put 30 men into the box cars. They were allowed to take their wives and children with them too. They were all shoved in, in rather a merry mood. They thought they were going to sunny Italy where they would be looked after and fed. We hid the Tito troops behind the station buildings. They only appeared at the very last moment and marched up and down and all the Chetniks started shouting and screaming and swearing at us. We hated it. It was so much against the tradition, particularly of the Brigade of Guards, to lie even to your enemies. They weren’t really enemies. They were simple peasants. One mustn’t think of these Slovenes and Chetniks as one would think of the German army. They were very young, some of them just boys with older men with their wives and some of them with their children. You were dealing not really with an army, you were dealing with thousands and thousands of civilians. I wrote a daily situation report. At the end of one of them I said that ‘our soldiers carried out this odious task with great reluctance’, which was perfectly true. But I got hauled over the coals for that. I shouldn’t have said it. But I think this was one of the most disgraceful actions that British troops have ever been asked to carry out.

(From a BBC Timewatch programme, 3 January 1984)

The despatching of more than 26,000 men, women and children to certain death began on 20 May 1945. These actions have been uneasily defended, by some, on the grounds that, at the time, Europe was in chaos and people scarcely knew what they were doing – not an impression one gets from Nigel Nicolson’s testimony. A more believable explanation for them is that Field Marshal Alexander, Allied Supreme Commander in the Mediterranean, and his political advisor, one Harold Macmillan, knew exactly what they were doing. In exchange for these prisoners, Marshall Tito pulled his five divisions out of Carinthia, Austria and Venizia-Giulia in Italy, which he was then absurdly claiming as part of Yugoslavia. 26,000 dead – what a price for some stability in post war Yugoslavia.

We drive up through the forest on route 917 which degrades into a dirt track with no room to pass vehicles coming down – but there are no other vehicles up here. It starts to rain and we ascend into a fog. We stop near the summit in a forest clearing next to an ancient disused sawmill. I lock up. We’re both exhausted and after a simple dinner we have an early night.

1st September 2022. There’s torrential rain overnight and a rising wind – weather conditions that are very loud in the van. In the morning the dense fog has returned. There was the possibility of climbing to the peak – but that’s not an inviting prospect. It’s a 17 km descent on a winding narrow track in awful visibility. So we wait. By 9am we’ve run out of patience, and the drive is surprisingly enjoyable. We call into the town of Kočevje and stop at a simple traditional restaurant where Jo orders a delicious hearty truckers plat du jour, an 11am breakfast of sausage and bean stew.

Slovenia has a short Adriatic coastline where there will be few if any options for free campervan parking so we turn towards the capital, Ljubljana. It’s still a gloomy grey day. We stop for a couple of hours at a laundrette and an Aldi supermarket then head towards the centre where we park in a big city centre car park and walk into town. It’s a delightful city: clean, friendly, historic, and lively, full of traditional bars and restaurants. The city is distinguished by a number of rivers that traverse it; the Ljubljanica, the Sava, the Gradaščica, the Mali Graben, the Iška and the Iščica. On Castle Hill above the centre stands the imposing medieval Ljubljana Castle. The old historic centre is unspoiled and despite earthquakes over the centuries, the wide cobbled streets and squares are lined with fine Gothic, Baroque and Venetian style buildings.

We visit a couple of cafe bars. At the Cafe Antico we sit at the outdoor terrace on the street and, over a couple of Lasko pivos (beers) and white wines, we watch Ljubljana citizens leisurely promenading in the evening sunshine. A young couple arrive on bicycles which they leave in the apartment block across the street. They wander across to the terrace for kisses, hugs and drinks with friends. Jo says ‘I’d like to spend a few months living in an apartment somewhere in Europe like this. What fun’. It’s a splendid idea. We cross a bridge to the Nostalgija vintage cafe for a few more beers and wines after which we can’t agree about the best route back to the van.

There are still a few after-tremors from the theft at Grad Otocec castle and our other tribulations, so the next morning we go our separate ways on the Brompton bikes. These fold up bikes are terrific and, despite the bone shaking cobbles, they’re the best way to explore a city like Ljubljana. Today is Friday and Open Kitchen ‘Odprta Kuhna’ is in full swing in the pretty Pogačarjev trg square. Ljubljana restaurants, and food and drink vendors congregate here to cook and sell delicious food. In a nearby square is a farmer’s market and in another a flower market. The sun is shining, it’s warm and the colours and smells are fantastic. I cycle along one of the rivers to find a print shop where I get a hardcopy of our vehicle insurance cover. The cobbled street to the castle is too steep for the bike. I walk up. The castle is largely under wraps for renovation so I immediately shake and rattle back down the hill. Near the central Prešeren Square I spot Jo cycling towards me. We have a big hug.

Slovenia has an abundance of picturesque lakes, the two most popular are Bled and Bohinj. Lake Bled is fairytale pretty with, in the middle of it, a Gothic church on an island. We pass it on the way to Lake Bohinj, located in a beautiful glacial valley in the Julian Alps. We stay here for a couple of days at a busy campsite, mainly full of younger folk in an assortment of campervans from hippy wagons to state of the art motorhomes, parked very close to each other around the perimeter of a big gravel car park. ‘No Parking Overnight’ in the wilderness is the rigorously enforced rule in Slovenia with steep fines for infringements. It’s not a big country and, with so many tourists, the opportunities for camping in the wild are few. Landowners ask as much as 30 euros to park overnight. Even for this scrap of land, they want 20 euros for a mobile home. The van is not registered as a mobile home, so we mischievously contend that it’s a car and stay for 4 euros a night. The views of the mountains, especially in the sunsets, are wonderful. We cycle through the hills and around the lake where we laze in the sun and swim in its clear warm water.

We drive to Kranjska Gora and our first sighting of Triglav mountain, the highest peak in Slovenia, before taking the 24km Vršič pass connecting Kranjska Gora in the Save Valley to Trenta in the Soča Valley, via 50 precarious, hairpin bends. There are some incredible views over the surrounding mountains and valleys. It’s a wonderful and at times exciting drive.

After 8km, just off the pass, there’s a simple wooden Russian Orthodox chapel, built in 1917 by Russian prisoners of war to commemorate their comrades who died in an avalanche during the road’s construction. The threat of avalanche continues to close the road during the harsh winter months. It’s very still up here, the silence punctuated only by the distant clanking of cow bells.

As the Vršič pass slowly descends into the picturesque Soča valley, the road flattens out and becomes a leisurely drive to Bovec. Here we see the Soča river, an ever-present accompaniment for the remainder of the pass. We stop at the gorge of the Soča where the river is clear and freezing cold and full of big trout. There are people swimming in the fast flowing waters. Are they mad? I spontaneously strip off down to my underpants and jump off a rock. It’s invigorating and brain numbingly cold. Further down river is the pretty medieval town of Kanal where, on a bridge 70 metres above the Soca river, there’s a jumping off platform. A young lad is standing on it, looking down, concentrating and swaying to and fro in anticipation. He jumps, his arms swirling to maintain an upright position. It’s a serious jump, beautifully done.

For the next stage of our Balkan journey please visit