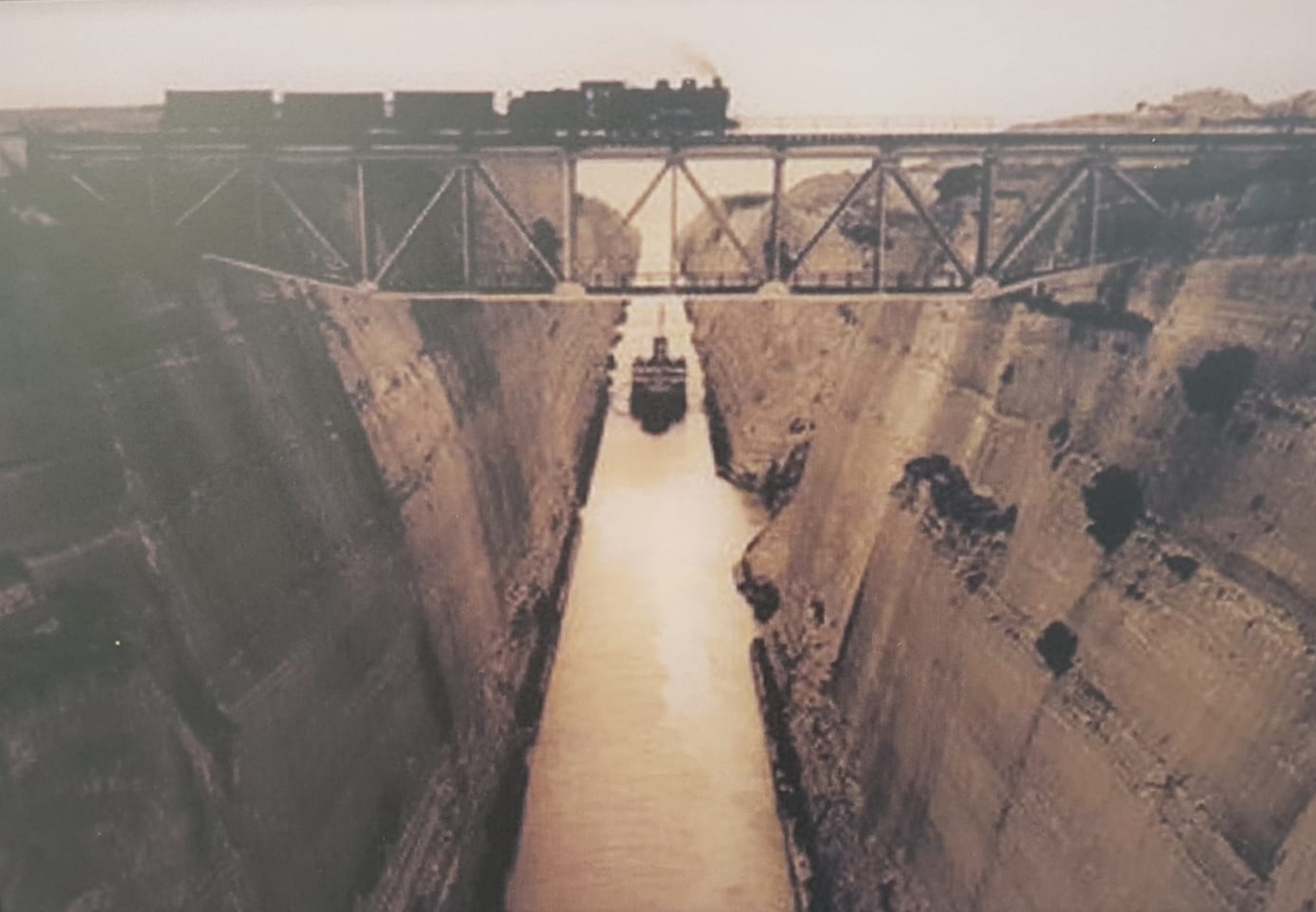

That scoundrel Emperor Nero was one of the first to conceive of, and attempt to build, the Corinth Canal. Legend has it that he personally broke the ground with a pickaxe and removed the first basket-load of soil in AD 67, but the project was abandoned when he died shortly afterwards. The Roman workforce, consisting of 6,000 Jewish prisoners of war, started digging the 50 metre wide trenches from both sides. The canal was dug to a distance of four stades, about 700 metres, or about a tenth of the total distance across the isthmus before work stopped.

Almost two thousand years later, in 1882, Greece commissioned a French company to start digging, but it went bankrupt. Eleven years later, in 1893, in partnership with a Hungarian construction team, the canal was finally completed.

1894

2020

The 4 mile long, 300 metre deep canal connects the Ionian Sea with the Aegean Sea. It cuts through the narrow Isthmus of Corinth that separates the Peloponnese from the Greek mainland, arguably making the peninsula an island. It’s impassable for many of today’s biggest ships. It has little economic importance and is mainly a tourist attraction.

It’s an impressive trench – a massive excavation. We arrive at a bridge that spans the canal, about half a mile from its northern end where there is a submersible bridge which we crossed earlier. A submersible bridge sits at about sea level, and functions like any ordinary bridge. But with the approach of a ship all traffic stops and the bridge sinks beneath the water allowing the vessel to pass overhead.

We’re standing on the high bridge over the canal when there is a remarkable apparition. An old four engined turboprop airliner passes above us, at low altitude, along the length of the canal. It sounds and looks like an aircraft of a bygone age.

In the distance, four vessels are approaching us: a speedboat, a tug pulling a tanker and a catamaran. We wait for fifteen minutes for the convoy to pass 300 metres below us. It’s a spectacular bird’s eye view. Nero would have been impressed. From far below, the passengers and crew give us a friendly wave.

Three years ago Jo and I visited the magnificent 2,400 year old theatre of Epidavros for a performance of Sophocles equally ancient tragedy, Electra. We swam in the small cove at Palea Epidavros, and it is to the beach on that cove that we have returned. We arrived on a Thursday and on the following Saturday, the Greek government imposed a three week Coronavirus lockdown. On lockdown eve we partied with a small crowd at the local taverna. Ten days later, we’re still on the beach and it’s the best possible lockdown imaginable. There are four other campervans here and we’ve made some friends. Jo has written about our stay here in her wonderful blog.

The campervan is parked sideways-on to the cove so that in the morning, before the church bells chime seven o’clock, I slide open the door to the red sun rising behind the mountain on the distant shore. This morning it is windless – the sea gently lapping onto the beach. Bees are hovering in the warmth of the early morning sunshine. There is a pomegranate tree behind us, heavy with ripe red fruits but it’s next to a bush alive with foraging bees so I can’t get to the pomegranates. An occasional rush of waves against the beach is caused by a small fishing boat chugging into the harbour or fishing around the cove. A solitary fisherman motors around in an arc, dropping his net. He then slowly retraces his route, retrieving the net. I watch him through binoculars, he doesn’t seem to catch much and a lot of what he does, gets thrown overboard, to the delight of scavenging herring gulls.

A tan and white bird flashes past and descends in the shoreline. It’s a sandpaper: a small, plump, very pretty, long beaked wading bird. She bobs like a wagtail whilst feeding and she bathes in the shallow water, meticulously preening her wings, tail and underparts before spreading her long pointed wings and fluttering upwards and away. A pair of blue and chestnut kingfishers dart past at sea level towards the rocky pine tree covered headland. Big silver fish leap from the sun sparkled sea, and smaller ones flounder along the water’s edge.

I observe this abundance of wildlife from my bed before I’ve even stirred for a cup of tea. This David Attenborough like nature watch is all well and good but I awaken one morning with a sense of urgency. We’ve done two weeks of a three week lockdown – a lockdown which will undoubtedly be extended with the possibility of stricter travel restrictions. We’ve recently had the occasional cool overcast day and the sunshine has been inadequate to supply the solar panel. We’ve needed to start up the engine for half an hour every day to keep the leisure battery topped up. We can’t stay here on the beach all winter. Our pre-lockdown plan was to be on the western side of the Peloponnese, in two weeks time, ready to take up residence in a house we have booked on the Mani peninsula. But I now feel that’s too late. We need to get into our accommodation now. We tell young Rhiannon, our campervan neighbour, of our decision, and within an hour we’re on the road.

I contact the owner of our intended residence, in Stoupa, in the Mani. I tell her of our situation and my wish to check into the house as soon as possible. She’s incredibly helpful and in 48 hours we will be guests in a fine traditional stone house on a hill above the village of Stoupa, overlooking the Messenian Gulf. We plan to be there throughout the winter.

As usual we avoid the toll roads and drive across the mountains for four hours to the west coast. We’re seeking somewhere isolated to stay for two nights before we can check into the house. We know the small coastal town of Gialova and we drive to the local wetland nature reserve for another brief Attenborough fix – it’s glorious: pink flamingos, white egrets, grey herons and a couple of striking Smyrna kingfishers. We drive beyond the birdwatching hides to a hidden sheltered beach where we stumble upon a young German family in their big motorhome. He is long haired and bearded, she is six months pregnant with plans to give birth in the van! Their three blonde youngsters are playing happily in the dunes.

We stay and talk to them for a couple of hours. I sense that he is keen for some, albeit distanced, human interaction beyond that of his family. The police know that they’re here, they call by occasionally to say hello. The young man is from East Germany, too young to remember the old communist regime but his parents would have lived under it. He is an intelligent and admirable idealist with ideas yet to be tarnished by harsh reality. Perhaps living long term in isolation, away from the challenges of the real world, allows one to live one’s ideals. We talk about democracy. His take on the perfect democracy is where the entire population does the same thing, such as everybody obediently going into lockdown. I tell him that I think that this is autocracy; the democracy I know is one where people disagree and argue (but there’s not enough arguing going on these days and way too much taking offence and cancelling). His children are tutored at home and he believes that all children’s’ education should, from the outset, take cognisance of their aspirations, strengths and weaknesses. We talk about lockdown; he is a disciplined advocate of it but he abhors the idea of test, track and trace. Of course, he hails from a country where people were historically tracked and traced en masse by the secret police, so his views on this are understandable.

I recently spoke with a friend about lockdown in the UK. He too is a disciplined advocate of shutting down society to ‘control the virus’. He talked about trusting ‘the science’ and the scientists who have recommended lockdown. I find this baffling. Science is about proposing a theory, testing that theory under controlled conditions, then challenging the results, publishing them in high quality peer reviewed journals where the data is available for public review and scrutiny, by the media and also by the scientific community. The SAGE scientist epidemiologists do not practice science. They make the numbers up, or base them on modelling, to use public-health parlance, that support their theories and they publish these numbers together with recommendations about how society must behave in order to avoid their worst case predictions. Anybody can produce a model to support whatever they want, and it should not be the remit of the SAGE people to make recommendations about how society should respond to their made up numbers. Even worse, their directives are made to purportedly control one disease. They’re not remotely interested in the appalling effects of lockdown on people’s physical and mental health. These effects include fear, the understated horrors of loneliness, suicide,depression, impoverishment, child and domestic abuse, lost education, and neglect of the symptoms of cancer and other killer diseases. The worst recession in 300 years, caused directly by lockdowns, will have a catastrophic effect on people’s lives.

Don’t get me wrong. Lockdown as a means of controlling the spread of Coronavirus does work. But the implications of this cure are infinitely worse than the disease itself. The original lockdown was understandable but with the realisation that that this pandemic is not of apocalyptic proportions, further lockdowns are unjustified. Tragically fear has taken over.

There are thousands of highly reputable epidemiologists and scientists who do not support lockdowns as a solution to the Coronavirus pandemic. See The Great Barrington Declaration The infectious disease epidemiologists and public health scientists who signed this declaration have grave concerns about the damaging physical and mental health impacts of the prevailing COVID-19 policies, and recommend an approach that they call Focused Protection.

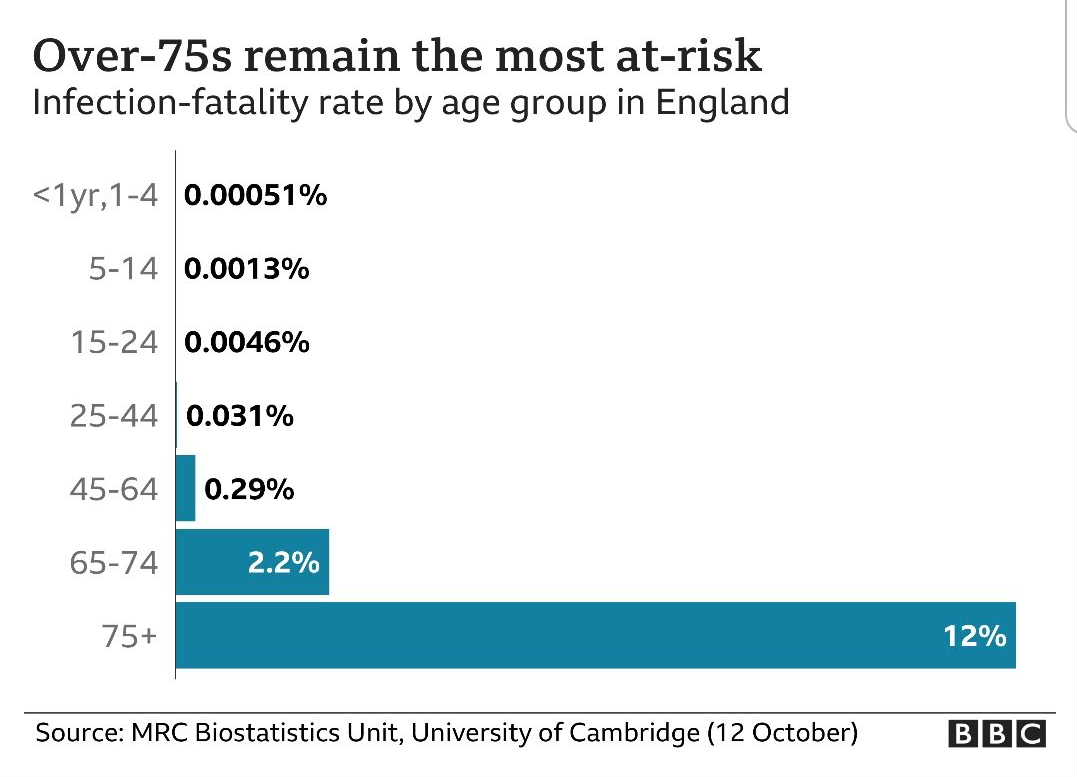

Look at the statistics below for the Covid infection fatality rate in England.

The infant death rate from Covid is 5 in every 10,000 cases, and that of 75+ is 1,200 in every 10,000 cases.

In Greece, of all the Covid fatalities to date, the average age was 80 years (96.8% had underlying health problems, or were over 70). So our approach to this pandemic is to give up our freedom and destroy people’s lives to protect the elderly. About 15% of the UK population is over 70. So 85% of the population is suffering to protect the elderly 15% of the population.

Clearly we should be protecting the elderly, but only the elderly, and those made vulnerable with threatening health conditions . Most of them are not in the workplace and many will not interact socially or travel as much as the young. Part of this sensible approach would also be to encourage the elderly them to protect themselves. Some won’t want to be protected and that is their right. As Kingsley Amis said, ‘No pleasure is worth giving up for the sake of two more years in a geriatric home in Weston Super Mare’. The rest of society should get back to work and play.

On the park4night app, I find a lonely, tiny chapel on a hill at the end of a rock strewn track. Its the perfect place to isolate before we check into the house. A previous visitor says that the journey to the top is ‘not easy and they were happy to have good tyres’. But we revv up the Ford and bump and grind to the summit. We spend two nights here and walk to a local waterfall. The walk begins as a boulder strewn path next to a river cascading down the hill as a series of beautiful waterfalls and rock pools. The path becomes narrower and steeper. our passage aided by iron rungs set into the rocks. It ultimately becomes a vertical rock climbing ascent. At one point Jo suggests that we retrace our steps but I’m not for turning back. We eventually emerge onto the track back to the chapel. On our last night here, it is warm, and we sleep with the van door open to the sound of jackals, some of the few surviving wild jackals in Europe, howling in the forest.

Tomorrow morning we will drive to the Mani. Some years ago I read a book by the author Patrick Leigh Fermor called Mani, Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. Anglo Irish Paddy is one of the 20th century’s finest travel writers. A scholar gypsy in his youth, in the 1960s he built a beautiful house on a remote cove on the west coast of the Mani where he lived for many years. He described a wild and beautiful narrow peninsula inhabited by equally wild Maniot clans who claim descent from the ancient Spartans. The region is often compared to the Scottish highlands, and there is a resemblance; remote, mountainous, often windswept. But let’s not get too carried away with this comparison. Amongst other things, the food, the wine, the citrus and olive groves, the warm Mediterranean sea and the climate are so much better.

The Maniots, over hundreds of years, built fortified towers and fought bitter and violent feuds with their neighbours mostly over land ownership. We will spend the winter in the northwest of the peninsula, a region called the outer Mani. The Taygetos mountain range runs down the middle of this finger of land. The foothills of the Taygetos are criss-crossed with hundreds of footpaths linking the ancient settlements. We shall walk many miles along those paths and, even though the locals will think us slightly bonkers, we’ll swim in the sea every day.

Hello! I just would like to give a huge thumbs up for the great info you have here on this post. I will be coming back to your blog for more soon.