In the early morning we enjoy a comparatively calm four hour bus ride from Mysore to the town of Chikmagalur, set in a valley of the Western Ghats. We’ve now travelled in a number of Government KSRTC buses. They’re all much the same: old, battered, with exposed welding joints and rivets, metal seating with torn covers, faded paint work, windows, sometimes perspex, often nothing, belching black exhaust fumes, grinding gears, very crowded, very cheap. They say if you wait long enough in India a bus will turn up for your destination. We don’t often have to wait long – and even if we did, an Indian street scene is rarely without entertainment to keep us diverted.

Sometimes there are women only seats, the use of which are not rigorously enforced. But to my untrained eye there is grouping and segregation going on – families and friends together naturally, but caste, gender and religious grouping too. I watch a Hindu woman ask a Muslim male, seated next to a woman, if he would please sit elsewhere. It was all perfectly normal and pleasant.

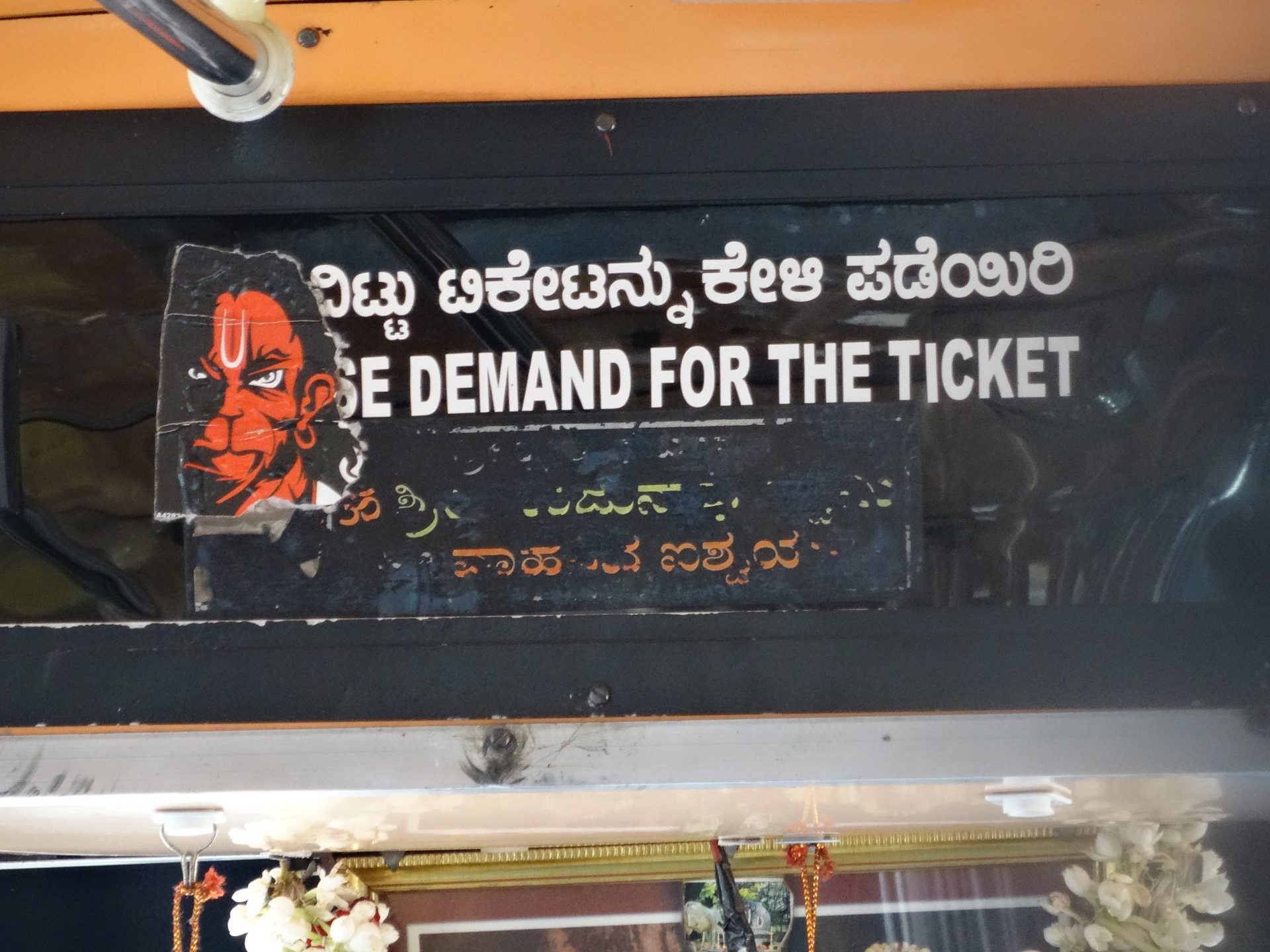

There’s always a conductor, so there’s an army of them at the bus station, shouting the destination of their bus and ready to point out the right one for you. We pay onboard and receive a ticket. On this bus is a sign next to the driver which reads ‘Please Demand For The Ticket’ The conductor doesn’t have a ticket machine. I ask him for one. He looks at me like I’m a fool, ‘No ticket,’ he says. The Times of India recently reported, ‘Forty people injured in KSRTC bus smash.’ I’d have thought it was a regular occurance not worth reporting – apparently not so. One was stolen last week – I wonder where they’re hiding it.

We hire a rickshaw at the railway station to take us to our Homestay. Gongu is the enterprising rickshaw driver and encourages us to book him for six hours the following day. He has an itinerary for a mountain trip. In the evening I send him a text asking about the possibility of trekking up to the highest summit in Karnataka. He replies ‘No tracking (sic).’ I ask ‘Why no trekking?’ His response is a short video of a tiger moving stealthily across a path into the bushes.’ This can’t be a common occurrence but there don’t seem to be any possibilities to trek accompanied, or not, in these hills.

The rickshaw tour is splendid. The mountains of the Western Ghats are formed into towering cliffs and dark brown rocks interspersed with waterfalls and verdant gorges. Gongu is a bit of an amateur wedding photographer – he knows all the best mountain viewpoints for honeymoon poses and he will persuade Jo and I to pose for loving couple shots. Jo has a list of places she wants to see in the Mullayanagiri Hills and they match up nicely with Gongu’s itinerary.

The rickshaw is the perfect vehicle for the narrow winding mountain roads. We climb the 464 concrete steps to the summit of Mullayanagiri where Jo is accosted for a photo opportunity with a group of Indian ladies. Gongu takes us to viewpoints and waterfalls. The sky colour today at altitude is ultramarine. On a hill of the same name is the Baba Budangiri shrine and small cave named after the Sufi saint Baba Budan, who is revered by both Muslims and Hindus. Something strange has happened here. The entrances to the Muslim part of the shrine and that of the Hindu, both down a long flight of concrete steps, are separated by fifteen foot metal fences topped with razor wire. This is to keep pilgrims of the two persuasions apart. Has there been conflict here? I think so but I can’t trace any reports of it online. The shrine itself is quite uninteresting.

This evening we treat ourselves to a bottle of L’Angoor Big Banyan Indian red wine – our first wine in five weeks. This twaddle on the label reads: ‘Taste the tropics in every sip of the cheeky red L’Angoor. This wine is heady with mischief.’ It cost £3, was medium dry and drinkable. We take a rickshaw into town (3 miles each way, £1.80 return) and dinner (£2). We are the only non-Indians in town and, in our local Chikmagalur eatery, English is not much understood. We were here at lunchtime when we caused quite a stir – chefs in the soot black open plan kitchen, waiters, and customers animatedly intrigued by us. When I tried to order a dish I was quickly surrounded by five waiters all keen to help. This evening, for 80p, I order the South India Meal which comprises a bowl of plain boiled rice, two fluffy rotis (I prefer the flaky paratha bread), a papadom, small steel dishes of curd, spicy vegetable curry, coconut based curry, dry chickpea curry and mango pickle. Strong black tea, no sugar, is 10p. Jo manages to make herself understood and orders an onion dosa with two curry dips.

Our homestay room has an enormous window overlooking a roof terrace, farmland, the foothills and mountains of the Western Ghats. At 7am in the morning I throw open the curtains to another beautiful day. I don’t mention the weather much, but I’m not taking it for granted. The February mornings and evenings are like the finest summer days in England under a clear azure blue sky. Jo is up for some morning exercises. I lie in bed watching the flocks of egrets and parrots fly towards me, away from their overnight roosts in the mountains. I like Chikmagalur very much but we only stay two nights. We have a one hour bus ride to Kadur followed by a six hour train ride (£1 each) northwest to Hubli. We are inching towards the ancient city of Hampi – today slightly in the wrong direction (not the way a crow would fly).

At Kadur railway station we must cross the tracks, via the bridge to platform 2. With our overweight bags this can be a tiresome and exhausting business. There are often escalators and lifts at Indian stations, mostly out of order But at Kadur, the lifts work. Jo settles down on a bench on the platform and I walk into town. Like the many semi feral pigs around here, I’m in search of food. I return with fruit, bread and coke to find that Jo has befriended some folks: a severely disabled young man – his limbs withered and contorted, the platform sweeper and her young daughter. Nobody is asking for alms but we share bananas and grapes and I give some cash to the man. Despite his disabilities he has a winning smile and advises us of the impending arrival of our train. I have many recollections of persistent, sometimes aggressive beggars in Northern India. Not so here.

I tell Jo how impressed I am that these South Western Railway branch lines in India are electrified. Fifteen minutes later the diesel engine pulling our train squeals onto platform 2. Despite being a Saturday the ‘express train’ to Hubli is not as crowded as anticipated. I spend time at the open carriage door watching the seemingly endless arable farmland. But mostly I sit here writing this. At station stops, food vendors and cheerful colourful trans women board the train to feed and entertain us.

The smell of rotting food, stagnant water and excrement is pervasive in India. The train passes a stretch of land where the odour is particularly bad. Face masks, hankies and scarves are whipped out by our fellow passengers. I’m wondering what all the fuss is about.The floor of our carriage is a mess of paper, plastic and tin foil food containers, bottles and miscellaneous trash. Mid way through the journey I’m really delighted to see a cleaner sweeping it up. ‘Oh good.’ says Jo. ‘He’s sweeping up this mess.’. He pushes an ever growing pile of rubbish up to the train’s exit door, where to my horror, he sweeps it all out onto the trackside. Much of India is encrusted by a layer of plastic. The final thermonuclear armageddon will compress it into a 5cm seam of hard matter that geologists will refer to as evidence of the Plasticene era. The scheduled journey time to Hubli is six hours. We’re on schedule, until ten minutes outside Hubli junction we stop at a red signal for an hour and twenty minutes.

Hubli is a bustling noisy city with no immediate appeal other than the rooftop swimming pool at the 4-star Phlox Hotel. There’s a restaurant up there too where, on the first night, we eat a meal that is not an Indian curry. The following night we’re back out on the streets for cheap local grub. Next time you’re in Hubli call into the basement cafe Hotel Haripriya for quality dosas. Don’t be deceived by the name. It’s not a hotel. There’s a clothes shop on the ground floor above it.

We encounter several people in town who want to know where we’re from, where we’ve been and where we’re going. A handsome young man, after making the usual inquiries, respectfully touches my knees with his fingertips, which he then presses to his forehead. This traditional obeisance towards an elder is swiftly accomplished in one graceful movement. It was over before I realised what was happening.

For the next stage of our Indian journey please visit Holed up in Hampi. Onto Badami, Karnataka State and into Goa.