We’ve just unloaded our bags from the bus at Madikeri bus station when a familiar voice calls out ‘Armand, Jo!’. It’s our fellow travellers from Donegal; Noel and Laura. We’re delighted by the coincidence of this chance encounter and to celebrate we agree to meet up later for dinner.

We’re booked into the Coffee Plantation Hotel – a 20 minute rickshaw ride out of town. Our room is disappointing. It was described as a ‘room with a balcony overlooking the garden’. This room is dark, the balcony is a foot wide ledge and it overlooks the access road to the hotel. So I complain at reception where the receptionist gets the manager on the phone. He tells me he’s sorry to hear that I’m confused about the room. I tell him it’s not me that’s confused and that I don’t like his tone – which changes quickly. He tells me we’ll get an upgrade tomorrow to a room overlooking the plantation.

We meet Noel and Laura at ‘29’ Bar and Restaurant near the bus station in Madikeri where there’s good food, music and an ominously extensive whisky menu of imported, locally bottled and Indian whiskies sold by the miniature. We kick things off with a sampling of four local miniatures. The barman senses the mood and flips his digital playlist to Irish pub songs. We share tales of life and travel and order four more different miniatures and then four more. We eat a very good curry and after another round, as if he knows what’s coming, Noel looks at Laura and says to me, ‘Ahh, she’s drunk now.’ I’ve lost count of the number of whiskies we’ve had and Laura (I think it was she) keeps ‘em coming. Noel and Laura nip out for a smoke and I join them. At a newspaper stall I buy a packet of bidis which I give to Noel. He’s not seen them before. Bidis are rough Indian hand rolled cigarettes wrapped in something like newspaper. ‘Jeez Armand.’ he says, ‘Do you know what bidis are in Ireland?’ They’re old women. I’m smokin a feckin old woman.’ Back in the bar there’s another set of miniatures on the table and the music has been cranked up. The ladies dance to Madonna.

Noel and Laura are getting married in Donegal in the autumn. We are invited to attend (it’s possible that I may have been asked to be best man or give the bride away). We’re definitely up for it.

It’s very late or very early but it’s time to go home. I negotiate a rickshaw for R300 and after kissing and hugging our friends, I pour Jo into the back seat and we head off into the hills. There are three men up front including the driver, a large bag of vegetables and a propane gas cylinder. Jo is leaning over the low side door of the rickshaw dispensing of her curry. I have a firm hold of her left arm – if I let go she’ll be gone. I’m very drunk but I don’t think we’re taking the most direct route to the coffee plantation. We’re zipping through the delightful backstreets of Madikeri dropping off passengers, gas and vegetables. Jo is moaning and gagging and seems to want to get off. I’m gripping her arm very tightly. After about 40 minutes we pull up at the sentry box at the head of the drive leading to our hotel. The driver jumps out and greets the hotel security guard. They stand there looking at, and discussing poor Jo’s condition. I’m not best pleased about this, shove the driver back into the rickshaw and order him to take us to the hotel entrance. Jo’s a dead weight but I manage to bundle her into the hotel and return to the rickshaw. It’s a right mess and the driver wants R1,000 to cover cleaning costs. I don’t argue. Somehow I get Jo upstairs, undressed and into bed.

We recover from last night’s shenanigans in our bright new room overlooking the coffee plantation which slopes away down to the river. Coffee plantations and tea plantations are completely different. Tea is a monoculture. The tea bushes occupy vast acreages of nothing else. But coffee plants need shade so they’re interspersed with trees – eucalyptus, teak, and rubber, upon which grow pepper vines and cardamom. These attract a healthy population of insects and birds. It’s a fantastic, symbiotic ecosystem that I’m enjoying watching with binoculars from the balcony. There are rollers, nuthatches, big red crested greater flameback woodpeckers, greater racket-tailed black drongos with a foot long elongated outer tail and two feathers at the tips. In the morning two pepper pod harvesters, a man and a woman, arrive with long thick bamboo poles, on which, along their lengths are small pegged steps. They lean these against the tree on which the pepper plant climbs and ascend slowly picking pepper pods – a laborious and delicate business.

Jo is suffering from some sort of toxic alcoholic contamination – hangover is too mild a description. On her upper left arm, as if she’s been assaulted, is a purple, brown and yellow bruise. She’s in bed, very quiet, occasionally drinking a small glass of water. It’s late afternoon before I set off up the road on a ten kilometre return walk through coffee plantations to the nearest shop. I return with a fresh coconut, nuts, chocolate, and a desiccated coconut cake. Jo drinks coconut milk and eats a little cake. She’s going to survive.

It’s a couple of days before Jo is really fit for travel and she’s reintroduced to it with another hair-raising bus ride to Kushalnagar, a town on the Kaveri river, 6 km south of which is the Buddhist Namdroling Monastery, also known as the Golden Temple. There are about 16,000 refugees living in the Tibetan settlement at nearby Bylakuppe and nearly 6,000 monks and nuns in this monastery, established after the Chinese invasion and annexation of Tibet in 1951. It’s the second largest Tibetan settlement in the world outside Tibet.

We arrive at the Golden Temple in the early afternoon. Approaching the prayer hall through the ornate gardens I can hear chanting. Inside the vast hall, adorned with vibrant Tibetan paintings, is a small roped off area for visitors. We sit on the floor, watch and listen as several hundred maroon robed young monks, under the guidance of their elders, sit in rows reciting prayers from manuscripts placed over small wooden tables in front of them. They chant to the accompaniment of deeply sonorous horns and very big gongs. The experience is calming and surreal.

I’m delighted that we decide at the last minute to visit Mysore. Mysore, with a population of 2.3 million people, has somehow avoided ballooning into an Indian megacity like Bombay, Calcutta or Chennai. So it can be assimilated and enjoyed without much hassle.

We check into the Pai Vista hotel in the city centre. It has a very good rooftop swimming pool which we enjoy in the afternoon. Every morning a free copy of The Times of India is delivered to our room, which I read before a swim and a very decent breakfast (there’s an egg chef). The Indian Times is a common sense and entertaining daily. I especially like their use of what used to be called Indish – perfectly good English but with idioms and verbs that are sometimes archaic, sometimes unfamiliar, and sometimes familiar but used in an unusual context Robbers and murderers invariably ‘abscond’ or are ‘nabbed by the cops.’ Every edition has an article or two about people being attacked by elephants (‘tusker tramples farmer’ or ‘marauding jumbo attacks village’) or mauled by tigers or packs of feral dogs. Crocodiles are popular too. Snakes don’t feature as death by snakebite is too commonplace. A 2022 study published in Nature Communications recently estimated that a vast majority of snakebite deaths globally – up to 64,100 of the 78,600 deaths – occur in India. But it has been suggested that some of these snake poison deaths are actually murder I’ve yet to see a snake here. Jo has seen a big spider. ‘How big?’ I ask. She holds up her fist. I laugh in disbelief. Violent crime can be gruesome – ‘man kills four relatives with sword over property dispute.’

There’s a Wanted Brides and Wanted Grooms page where partners are sought by caste, religion, language, profession, nationality and community. ‘South Indian Brahmin Boy, 35, familiar with North culture, vegetarian, fair, 5’ 6”, bank manager, new at Bangalore. Seeks any Brahmin girls.’ or ‘Match for North Indian settled in Mumbai. Beautiful working Rajput girl, 1991, 5’5”. Wheatish (lighter shaded brown skin). Convent educated. Post Grad.’ This is inclusivity and diversity with a twist.

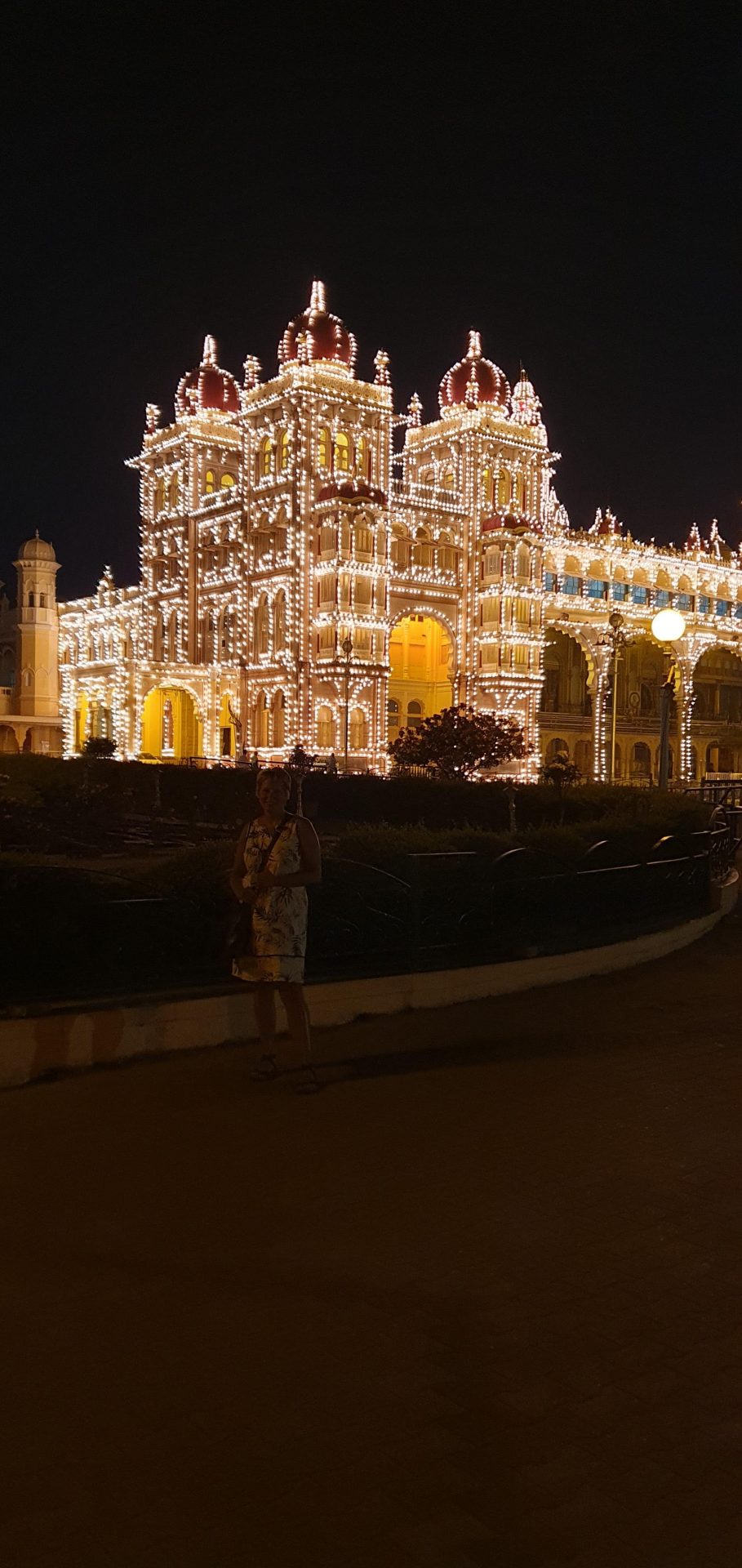

Walking to Mysore Palace, Jo is pestered by a drunk who, despite me intimidatingly staring him down and gesticulating f**k off, keeps following us. Jo senses drunken malevolence around us. We enter the palace grounds for a one hour son et lumière. It’s a Wednesday so the narrative of the history of Mysore is, I think probably in Hindi. But who knows. Millions of people in Karnataka speak Kannada, the official state language. Other languages spoken by significant numbers are Telugu, Urdu, Marathi, Tamil, Tulu, Konkani, Malayalam, Banjari, and, in the Coorg, Kodagu. Despite me not understanding a word, the narrative is nonetheless entertaining in a pantomime style – much galloping of horses, screams and sonorous declarations from the villain. The illuminations are disneyesque – at the end of the show the magnificent palace is reduced to a kitsch magic kingdom with 100,000 light bulbs.

The next morning we visit Mysore Palace again to see the inside. Once the official residence of the Wadiyar dynasty and the seat of the Kingdom of Mysore, it was constructed relatively recently, between 1897 and 1912, after the old palace burnt down. Today it is India’s most visited heritage destination after the Taj Mahal. The inside is genuinely magnificent – vast pillared halls of gold, silver, stained glass and teak ceilings. The scale is stupendous as is the fantastic intricacy and delicacy of the carvings and wall and floor tilings. One hall is surrounded by wall paintings of military parades that recall the spectacle that was played out before a huge auditorium open to the parade ground on which the Maharaja’s forces accompanied by elephants, bulls, horses and camels, would have presented themselves. In another hall hang portraits of previous Maharajas. Here too are portraits of the British monarchs, King Edward VII and Queen Alexander. But they are propped up against a wall, suggesting to me a half hearted enthusiasm for their presence or the possibility that they might be packed off at short notice.

We visit Wellington House for which there does not seem to be much enthusiasm either. It’s an odd looking two storey building lacking imperial embellishments. Part of the ground floor is presently a museum dedicated to the northern nomadic tribes of India. The remainder is semi derelict, semi building site. I wander up an outside staircase to the first floor. Nobody is working and an unfriendly functionary ushers me out. Assorted Hindu statues are scattered about the unkempt gardens where bits of wrecked cars are overflowing the wall from the scrapyard next door.

Built over two hundred years ago this was the residence of Lord Wellesley – later The Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. Wellesley, together with the resources and armies of the British East India Company defeated Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore, and destroyed his capital Sirangapatnum, just outside Mysore in 1799. As William Dalrymple writes in his wonderful and sometimes shocking history of the East India Company: Anarchy. The Relentless Rise of The East India Company.

On 19 February 1799, the four East India Company battalions in Hyderabad under Colonel James Dalrymple, along with four further battalions of Hyderabadi sepoys and more than 10,000 Hyderabadi cavalry, joined up with General Harris’s Company army. On 5th March, with some 30,000 sheep, huge stocks of grain and 100,000 carriage bullocks trailing behind them, the two armies crossed the border into Mysore there followed at least 100,000 camp followers, who outnumbered the combatants by at least four to one…it trundled at at agonisingly slow pace of five miles a day, stripping the country bare ‘of every article of subsistence the country can afford’ like some vast cloud of locusts.

On 5th April the army came within sight of the great walls of Srirangapatnam outside Mysore. It took nearly a month of artillery attacks to breach these walls.

On 4th May, at 1pm, in the intense heat of the day, Sir David Baird roused himself, gave his troops a rousing cheer and a biscuit, and drew his sword saying, ‘Men are you ready?’ ‘Yes.’ was the reply. ‘Then forward my lads.’ Tipu Sultan was shot at point blank range through the temple and within a few hours the city was in Company Hands.

The Mysore casualties were huge.10,000 of Tipu’s troops were dead as opposed to around only 350 of the Company’s men.

That night the city of Srirangapatnam, home to 100,000 people, was given over to an unrestrained orgy of rape, looting and killing Arthur Wellesley told his mother, ‘Scarcely a house in the town was left unplundered….I came in to take command of the army on the morning of the 5th and with the greatest exertion, by hanging, flogging etc etc, in the course of that day I restored order’

The best lands of Mysore state were divided between the Company and the Nizam of Hyderabad. The rump was given to the Hindu Wadiyar dynasty, watched over by the British Resident. The Wadiyars moved their capital back to Mysore where they remain to this day. The once great city of Srirangapatnam is now mostly grazing land.

Might the neglect of Wellington House have something to do with contempt for the British Raj or is it just the lack of funds and a general disinterest. I think the latter.

British Imperialism in India, like all Imperialism, is complex. Despite the common uninformed (one sided) narrative, the British made some magnificent contributions to India including establishing the foundations for the biggest liberal democracy on earth. It is politically correct in India today to suppress any positive aspects of the British Empire. This denial can sometimes reach laughable proportions. I watched a senior Indian politician declare on television, ‘…but of course everybody knows that it was India that introduced cricket to the British.’ You have to appreciate just how much cricket means to the Indians to understand the enormity of that lie. But there were some terrible indefensible cruelties motivated by avarice and power lust. And at the end the bloody chaos of independence and partition.

Not least of the horrors conferred upon India was the East India Company (EIC) – an organisation with stock issued to shareholders in the City of London. Imagine Google conquering the world with the aid of an air force, army and navy. At the beginning of the 17th century India had a population of 150 million people – about a fifth of the world’s total. It was an industrial powerhouse producing a massive quarter of all global manufacturing, mostly textiles. In comparison, England was a relatively impoverished, largely agricultural country, producing just under 3 percent of the world’s manufactured goods.

Dalrymple’s Anarchy. The Relentless Rise of The East India Company describes how the EIC, a single business operation, based in one London office complex set about the ruthless seizure of this India’s economic wealth for its shareholders, and managed to replace the mighty Mughal Empire as masters of the vast subcontinent between the years 1765 and 1803.

A rickshaw driven by Ishmael ‘call me Smiley’ takes us to the Old English Market where we wander amongst the ancient stalls of the fruit and vegetable market. We are now tourist captives of Ishmael but we don’t mind. He drives us to Sharif Incense and Essential Oils Emporium in the old town where we see a woman making joss sticks by hand. I buy sixty of them: nag champa, sandalwood, jasmine. We buy essential oils, jacaranda, water lily (excellent mosquito repellant) and jasmine.

Smiley then drops us off at the Devaraja market – a covered market selling a fantastic array of fruits, vegetables and flowers. Flowers bring colour to Indians’ everyday lives, as well as being part of major life events. The region boasts fertile soil that produces more than 75% of all the flowers sold in India. The 120 year old market opens at dawn every day of the year. It has some 150 flower vendors, offering chrysanthemums, jasmine, roses and other blossoms sold in bulk or in garlands for women to wear, honouring the gods or celebrating rites of passage. It’s an entire community that lives and thrives around the bustling flower trade. The colours, the arrangements and the sweet aromas are fantastic. We walk through the banana hall in which are tens of thousands of green, yellow and red bananas of all sizes hanging from the rafters and piled on the floor. Hundreds of crows, Brahminy and brown kites circle over or sit on rooftops above the foul smelling outdoor meat market, looking out for scraps of meat.

Kites are India’s new vultures. The Indian vulture, once commonplace (I recall seeing, many years ago, a flock of vultures gorging themselves inside the carcass of a horse on the Maidan in central Calcutta), is now under threat after a rapid and massive population decline in the last few decades, from about 40 million to only 19,000. The cause is the widespread use of drugs such as diclofenac – now banned in India – a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID drug) similar to ibuprofen which is fatal to vultures. It was once commonly used to treat livestock. Animal carcasses formerly eaten by vultures now rot in village fields leading to contaminated drinking water, and the disappearance of vultures has allowed other species such as rat and feral dog populations to grow.

For the next stage of our Indian journey please visit Chikmagalur and Hubli, Karnataka State.