It’s our second day in Greece, a fine clear warm day. We’re having some difficulty finding the police station in the coastal town of Egio. It’s a thing we’ve discovered about Google Maps in Greece – it’s not particularly accurate, either because of deficiencies in the original mapping process or because it’s not updated. Real world roundabouts are absent on the App and the Google police station in Egio is, in reality, an abandoned office block.

But Google Search gives us a police station and a street name and soon Jo spots a municipal building flying the Greek flag. Inside, the Egio Nick is like most police stations; big heavy doors, drab grey paintwork and terrible lighting. The electric fittings are unfinished, bare wires poke out of walls and ceilings.

A big, gruff unshaven plain clothes cop looks down at us and, without introduction, points to a bench against the wall and commands ‘SIT!’. He then commands ‘WAIT’. I feel like a dog at training school. We wait. We’re opposite an open door, leading to an office, in which an interrogation is in progress. Not an interview, a full blown shouting, accusatory slanging match. After some minutes an attractive young, plain clothes cop appears, the interrogator I think. He’s wearing a face mask but his eyes are sympathetic. We briefly outline what has happened to us. He apologises in confident English and explains that he has some urgent business to attend to. Would we please return in an hour.

As I said, this was our second day in Greece. We arrived on the Ancona, Italy to Patras ferry only yesterday. Operated by the Greek ferry company Anek Superfast LINK (for an efficient booking service and access to various discounts, call ferries.gr on +30 281 034 6185), it’s a brilliant service: clean, efficient, friendly. We booked a comfortable cabin with WC and shower on the brand new Superfast XI ferry for a 21 hour (2 hours ahead of schedule) crossing of the becalmed Adriatic Sea. I reckon the ship was only at about 10% capacity so there were no issues with social distancing. The breakfast of bacon, eggs, tomato, bread roll, fresh orange juice and proper coffee was fabulous (but not cheap).

It’s a real delight to be in Greece. We are heading east along the coast for about an hour to the small town of Diakofto. With mountain vineyards to the south and the bay of Corinth to the north, it is described as a busy, attractive little town with a unique narrow gauge rack and pinion railway line creeping through a gorge, up to a ski resort and the town of Kalavryta. There’s a small pebble beach outside Diakofto where we will park for the night.

On the drive along the coast we stop at a red light where we are approached by a young woman, without a mask, begging for money. No, she’s not simply begging, she’s pleading. I shake my head. She slaps her palms on the window. We don’t make it through the green light and she’s back again imploring yet more insistently. I’m not persuaded and at the next green light I pull away.

Jo and I discuss the pros and cons of giving money to beggars. Jo feels bad, guilty, about what has just happened. I’m more heartless. We gave food to a Greek guy begging at the port in Ancona. We gave fruit to a begging pilgrim in France. I’ll give money to a busker or a street artist but I won’t give money to a beggar especially if they try to bully me and play the game of trying to make me feel guilty. I’ll only relent if the situation starts to get threatening, something I’ve experienced in India.

Our parking place for the night is not the best site. There’s a lot of rubbish and dog faeces about but it will do for tonight. A Dutch woman, a solo campervanner, comes over for a chat. There are a few other campervans parked up nearby, mostly Germans. We cycle to a restaurant that we passed near the little harbour by the town, where we enjoy our first Greek meal; tzatziki, fried sardines and fried squid. We toast our good fortune.

The following morning, we start the day with a swim in the bay, a tidy up of the van and a walk into town for a coffee and a few provisions. Tomorrow is a public holiday celebrating Ohi day – the 28th October 1940 when the Greeks refused an ultimatum to surrender from the Italian fascist Benito Mussolini. The Greeks took to the streets shouting Ohi! (No!). They were not to be bullied either.

After spending a couple of hours in town we’re walking leisurely along the beach when I spot a pair of black trousers and a black bag floating in the breaking waves. I joke about finding a body that will spoil our day. Jo light heartedly says they look like her jeans and she hopes we didn’t park too close to the water’s edge.

Back at the van I unlock the five super secure deadlocks on the van doors and open the central locking. Jo opens the rear tailgate and I open the side sliding door. I notice that the duvet and covering blanket are awry and our two laptops are on the bed, not on the Brompton bike boxes, on the front seat, where we left them. From the rear of the van Jo says that our storage washbags have fallen out of their shelves. Something is not right. We speculate bizarrely: has a sudden breeze rocked the vehicle? We KNOW the van is secure. We don’t conceive of the possibility of a break in. Then Jo firmly declares that bags are missing. We have been robbed. I check all the doors for damage or any signs of a breakin – nothing. I look at the two small side windows. The nearside window has two small, almost imperceptible marks where, to effect the prising open of the window clasp, the paint has been removed by some sort of small tool. That window has been forced open. But it’s tiny, 31cm x 31cm. Entry through it could only be gained by a child.

Some of the bags left behind by the thieves. Only a child could get through that window.

So they broke in through the window and put a child into the van to grab what it could. These were not sophisticated thieves, hence leaving the computers. As the doors were deadlocked, they could only steal what they could pass through the window. They took four pairs of shoes, a bluetooth speaker, and five washbags containing socks, underwear, toiletries, cosmetics, stationery, nothing highly valuable, but it all adds up to the hassle of an insurance claim of over €1000. The thieves didn’t desecrate the place, they were just hasty. They even closed the window after them. But we have that feeling of being violated – we must wash all the bedding. And we feel momentarily insecure.

We’re back on our SIT! and WAIT! bench at the police station. The previously open door opposite us is now closed. We wait. I knock tentatively on the door. No reply. We wait. I get up and open the office door. Our handsome Greek cop is at his desk. Come in. Come in. He says. Please sit. He’s busy at his computer, the interrogation case I think. Thank you for being so patient he says, I must just finish this. I’m happy to wait. After about an hour we’ve completed a deposition which he says will be typed up and ready for collection the day after tomorrow’s holiday. His name is Nikolai. He’s the nicest Greek cop in Greekland.

With our police report we must make an itemized insurance claim. I look at the list of stolen items and I feel momentarily sorry for myself. I have one decent pair of shoes, one pair of walking shoes, and a pair of flipflops. My decent shoes were a very nice pair of brown leather Loakes (replacement cost £240) and the child nicked them. I’m 65 years old and like an impoverished African I now don’t own a smart pair of shoes. But I’m cheered up quickly on several counts: I have big size 11 feet, too big for most Greeks, so those shoes are pretty useless to the thieves. The insurance claim should pay to replace them, and they’re only a pair of shoes – far worse, the van could’ve been stolen.

We don’t feel good about staying over at the scene of the crime, so we drive up the coast and park outside a restaurant on a more salubrious stretch of beach.

Some afterthoughts: We think back to the beggar at the traffic lights. I’m not superstitious but is there perhaps some karma at play? If you fail to give voluntarily to the poor and the dispossessed then the poor and the dispossessed will take from you. And we realise that those were indeed Jo’s trousers and her black shoulder bag that we saw floating in the surf. We go looking for them, as far as the little harbour, but the current has swept them away.

The next day, we sit out the wet public holiday at our new beach site. The cloud formations over the Bay of Corinth, especially in the late afternoon and towards dusk are spectacular. At twilight a gradually enlarging flock (a murder!) of crows, two hundred or more, gather to roost. They swoop around as if choreographed to eventually settle in a copse by the sea. We are in a much better place.

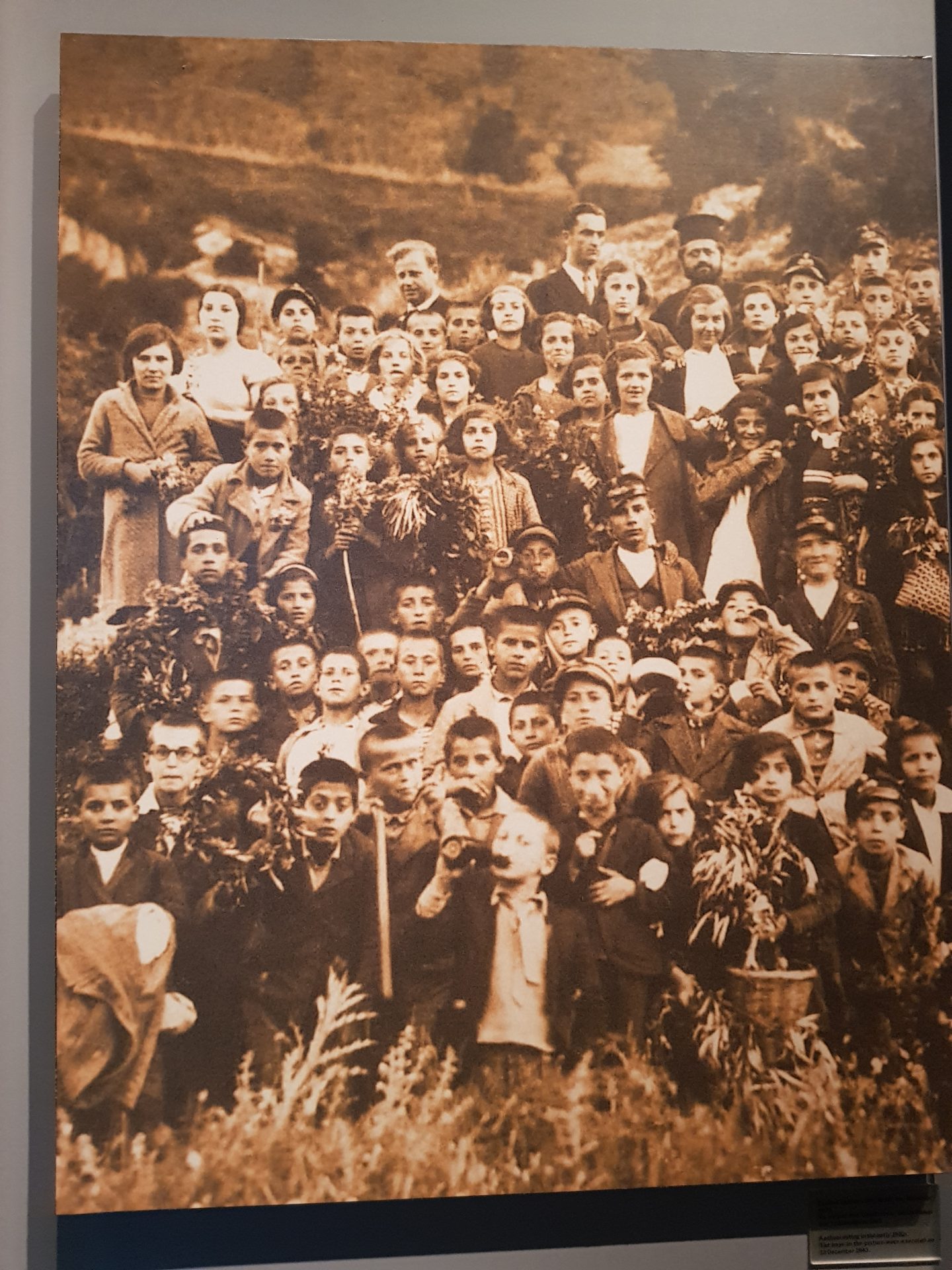

The following morning, and the Greek sunshine has returned. Back at the town of Diakofto – where we were broken into – we park next to the railway station. Jo, being ever resourceful, has bought a hacksaw and used it to cut two metal rods for window locks, preventing them from sliding open. A thief would now need to smash their way into the vehicle. I ask the station security guard to keep an eye on the van and we ride the train up through the gorge to Kalavryta. There’s an excellent and very moving museum in the old village school commemorating the barbaric massacre, by the Germans, of the village’s adult and adolescent men during the second world war. We buy some local wine and a big jar of orange blossom honey.

A photograph of school children from Kalavryta on a school trip. Most of the boys in this photo were killed by the Germans.

After we’ve collected our crime deposition from the police, we head back up into the hills. We park next to a tiny chapel at the end of an avenue of small fir trees, overlooking the bay, the village below and the surrounding olive groves and vineyards. Other than a walk down the hill to the Tetramythos Winery, we stay right here, undisturbed, for three nights: writing, reading, cooking and sunbathing. Every night after dinner we light a small fire to dispel the late evening chill.

Forty years ago, the most prevalent and sometimes only available Greek wine was Retsina; a yellow, sour, almost oily wine. After an enjoyable wine tasting session at the Tetramythos Winery we buy a bottle of Retsina, a crisp white Roditis grape wine and a Cabernet Sauvignon. The Retsina is aged in big clay amphoras with a pine cone, to impart the resin flavour. It’s a fabulous wine – just don’t buy a cheap one.

Wineries and winemaking have grown and improved dramatically in Greece over the last twenty years. Our wine tasting guide at Tetramythos Winery tells us that EU support has been critical. Greek viticulture is niche, almost exclusively organic and relatively small, with its own unique grape varieties. This winery was started by two brothers in 2004. In 2008 the winery, their homes, vineyards and thousands of hectares of the surrounding countryside were destroyed by forest fire (the flora is still visibly immature). But they rebuilt their homes and a fabulous winery from the ashes. I’m full of admiration for their courage and determination. Our wine tasting guide gives us a map with almost fifty Peloponnese wineries on it. We’ll start tomorrow.

A very sad and scary story.I am very glad you are both ok.😡🍹💕💕

Superb as well as very amazing blog site. Will certainly read a lot more

from now on.